The really good news about oysters is that unlike other seafood delicacies, they can be sustainably farmed without negatively impacting the environment. Meet the underwater farmers doing it right.

September 25, 2014

Ask a foodie to name the single best gourmet sea edible and there’s a good chance you’ll hear oyster as the response. Oysters are enjoyed like fine wine, with a complement of subtle flavors that play out over the palate. Oysters arrive at the table as fresh as a food possibly can. And since their taste comes from the water they grow in, oysters offer a regional flavor that few foods can match.

The really good news about oysters is that unlike other seafood delicacies, they can be sustainably farmed without negatively impacting the environment. An emerging cadre of young farmers are doing just that—turning to the estuaries that once teemed with wild oysters to raise the succulent bivalves in their native waters again.

Underwater Farmers

Meet Jules Opton-Himmel—one of these new underwater farmers. As a child in New York City and later as a graduate student at the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies, he was always an avid outdoorsman. “When I was in New Haven, I had an interest in going clamming in Long Island Sound,” Opton-Himmel tells Organic Connections. “So I looked up the regulations on the Connecticut Department of Agriculture’s website and happened to notice that you could lease underwater land tracts at a starting bid of something like two dollars an acre.”

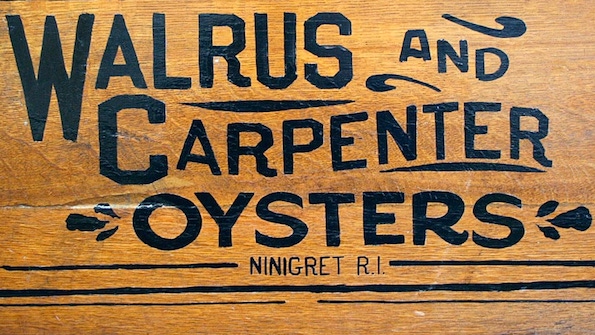

After college, Opton-Himmel worked with the Nature Conservancy, researching submerged lands and restoring shellfish populations, before deciding to go into farming for himself, founding Walrus and Carpenter Oysters (the name is an Alice in Wonderland reference) with a friend. He now raises oysters in three acres of waist-deep water in a southern Rhode Island lagoon called Ninigret Pond.

Opton-Himmel highlights the environmental value of farming oysters by pointing out that only a fraction of the wild oyster population from a century ago still remains. “Harvesting them would be like harvesting the last dinosaurs,” he feels, not a great long-term plan.

Farmed oysters, on the other hand, offer a sustainable crop that doesn’t have any adverse impact on the wild population and doesn’t damage the environment where they’re grown. “Oysters and other bivalves are the most sustainable kind of farmed seafood because you don’t have to feed them,” Opton-Himmel indicates. “With fish, you have to feed them corn or other fish. You add nutrients to the system and end up basically polluting what would have been a pristine system.” With oysters none of that is an issue because all their nutrients are derived from the water they grow in. “We don’t use any pesticides or herbicides either,” he adds.

Farming Oysters

Unless the farm has its own hatchery, baby oysters typically arrive as “seedlings,” which are 1-millimeter-sized oysters that have already formed shells. A two-liter container typically contains about 1.5 million oyster seedlings. These go into something called an upweller, “which is basically an underwater greenhouse for oysters,” Opton-Himmel explains. “For the first month of their lives they’re in there.

We stir them every day and begin separating them by size every week and bringing the bigger ones down to the farm.”

There, the oysters are kept in mesh bags anchored in the waist-deep water. Raising them is labor intensive, with most of the workday taken up by cleaning and sorting the shellfish so that the bigger ones don’t outcompete the smaller ones. “We have two to three million individual oysters, so it takes a lot to keep them happy, growing and alive,” Opton-Himmel says.

The largest oysters are kept in trays at the bottom of the water, where their advanced size generally keeps them safe from crabs and other potential predators. In a year and a half to three years they start becoming big enough to harvest.

Walrus and Carpenter Oysters distributes directly to about twenty-five restaurants in Rhode Island as well as to a few individual customers in nearby cities.

Farm Dinners Hit the Beach

Last year, Walrus and Carpenter began hosting “farm dinners” during the summer. “The goal of the farm dinners was to strengthen our relationship with some of the chefs we supply by showing them the farm, and also to educate the general public about what we’re doing and why it’s good for the environment,” relates Opton-Himmel.

“Oyster farming is a totally foreign concept for a lot of people, even the ones who enjoy eating oysters. So, we created these dinners where we get different chefs to come down and prepare a four-course meal on the beach. First the guests get a tour of the farm in our workboats, which is funny because they come all dressed up and our boats are pretty nasty. We show them how the farm works and why it’s good for the environment.

“We have a raw oyster bar in the water,” Opton-Himmel continues, “so everyone gets out of the boat and we shuck oysters and pair them with wine or Prosecco, and the guests can throw their shells into the water, which everybody seems to like.

“There’s a beautiful beach behind the farm, and we go there for the four-course meal.”

Opton-Himmel says that in appreciation for the support his business has received from the local food movement, 100 percent of the proceeds from one of this summer’s dinners went to the Southside Community Land Trust, an organization that helps urban communities gain the resources to grow food for themselves in Greater Providence, RI. Opton-Himmel adds that he hopes to have more charitable events like this in the coming seasons.

Learn more about Walrus and Carpenter Oysters.

You May Also Like