Looking out across the attendees at a NoCo Hemp Expo, Oregon hops farmer Mark McKay speaks of the hemp growers in attendance when he waves his hand across the crowd and declares, “in two years, all of these people will be gone.”

McKay has done little more than dabble in hemp farming by giving his son some acres on the family’s 550-acre Williamette Valley farm, but as a fifth-generation farmer, he knows something about how agriculture works. And what he knows tells him that the economics of growing hemp are not likely to be kind to farmers with smaller acreage and smaller resources, especially not when those farmers don’t have years of experience. Established farmers with the acres, the equipment and the experience are going to beat the small farms and newcomers on price and efficiency, he says.

“You don’t need many 2,000 or 4,000-acre guys to swallow a whole industry.”

That conclusion could be jarring to the voices heralding hemp as the savior of the family farm. In that vision, hemp is a lucrative lifeline that could wean growers on smaller farms off the doomed economic spiral of commodity crops and restore vitality to rural communities. That’s not what McKay sees when he looks at hemp. “Hemp’s going to have its day for a couple of years, and then it will get into the hands of the big guys,” McKay says.

To be clear, nobody said it was going to be easy, and even people who support the vision of restored rural economies see the challenges as formidable. Erica McBride-Stark, executive director of the National Hemp Association, won’t dismiss McKay’s daunting predictions and says the goals of organizations like hers won’t be accomplished without hard work coordinated between growers, processors and brands. “That’s what I’m hopeful for,” she says, “because certainly one of the main reasons that we fought for this for so many years is to benefit the small and medium-sized farmer.”

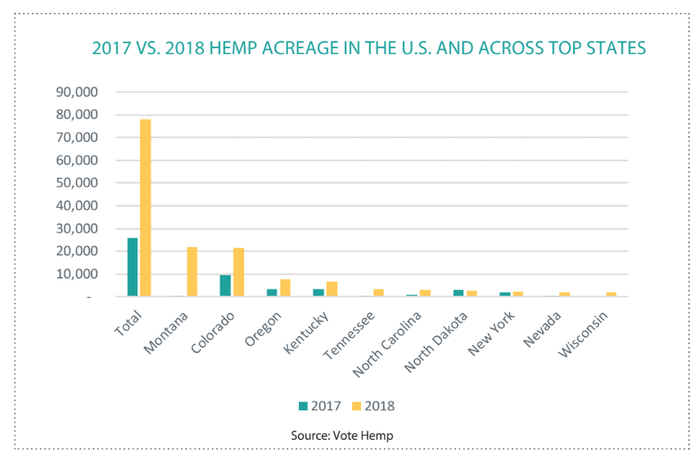

In McBride-Stark’s view, there’s still runway left for small farms. Indeed, she says, even beyond the regulatory issues that have kept big players out thus far, industrialized agriculture has little reason to enter the fray just yet. There’s no hemp shortage looming, she observes. “I actually am more than a little bit concerned that supply and demand might be a little bit out of balance with how many more people are cultivating this year than have in the past.”

Such dynamics mean many farmers’ dreams may not be realized in the short term, but McBride-Stark says getting enough farmers into the business early was always part of the plan. “Our hope in this from the beginning was to have the small- and medium-sized farmer get enough of a foothold into the industry to be able to keep up with demand and that it won’t get to the point where Big Ag sees stepping in as being advantageous.”

Fiber and seed oil are different business propositions where scale has more advantage, McBride-Stark admits, but she believes the small farms that she’s talking about are producing for the CBD market, where quality eclipses economies of scale. “For CBD processing, I think that the small- to medium-sized farmer is going to have a pretty good beach in this market for quite some time.”

Green rush mentality

Veronica Carpio, the hemp-farmer founder of Grow Hemp Colorado and an outspoken voice for the potential of hemp as an economic benefit for rural communities isn’t so sure. She tells a story about a Chinese company buying land in Nevada to build greenhouses where they would grow hemp to supply GW Pharmaceuticals, makers of the only FDA-approved CBD drug, Epidiolex. American farmers could have supplied the hemp, she says. They weren’t asked. “They weren’t contracting with farmers, but they were buying up land.”

What Carpio sees is a “clear division” being defined in the hemp industry between growers and processors who are ready to see the hemp industry monetized and professionalized in a big business model and “another side who says everybody should benefit; the whole should benefit.”

That “everybody should benefit” model is at risk, she says. “Do I think the old schoolers that were part of this movement realized it was going to be corporately controlled? Hell, no. Do I think people involved now who are the self-proclaimed leaders of hemp know the possibilities of big corporate and Big Pharma taking it over versus fighting for the medium and small farmers and fair regulation? Yeah, I think they’re well aware of it.”

In the ground

Whatever the intentions, the practicalities of growing any crop at scale requires a level of expertise and resources McKay is convinced many in the current crop of hemp farmers don’t possess. Hops is a small crop in the scheme of things, but the investment is no small matter. McKay says hops farmers like him could step in and put those investments to bear in a way that would put much of the current hemp farming operations out of business. “The dryers are in place and the harvesters are in place,” he says. And that part of the equation doesn’t even account for the years of experience.

Drying operations alone cost millions, he says, and he gets calls from hemp farmers every day who want to use his drying equipment. He assumes most of them haven’t thought the process through. “I’m saying, ‘You have crop in the ground and you don’t know where you’re going to dry it?’”

The hops industry already has the extraction facilities too, he points out, a capacity that many in the hemp industry worry is in too short supply. “We’ve got the infrastructure in place. It’s just a matter of putting seeds in the ground,” McKay says. “We’d kill the market in one year.”

CV Sciences Director of Hemp Production Josh Hendrix doesn’t dismiss McKay’s warnings entirely. He foresees a commodity market for fiber and grain with all the negative connotations of “commodity,” but for the CBD market he sees “an opportunity to not let it become a bad commodity."

“I don’t necessarily think right now that hemp grain or hemp fiber is what people are talking about when they say this is good for the small farmer,” Hendrix says.

“We have an opportunity to do it the right way so there’s still value to the small farmer,” he says. Part of that is a matter of timing. Hemp has a “new, hip, cool thing” quality right now that dovetails nicely with the buy local/buy organic movement in terms of audience overlap, Hendrix says. He talks of it as a “gateway crop” that tugs conventional farmers into the organic space. That overlap and that first-mover factor could be enough to keep hemp-for-CBD in the hands of family farmers.

“The way I look at it with hemp is that Big Ag hasn’t taken an interest, so there is a door open for small farmers to come in and take the first-mover opportunity.”

Organic origins

John Roulac thinks what Hendrix describes is possible. He’s just worried that it’s not being realized. Roulac had a career in natural products founding NUTIVA before he founded RE Botanicals, basing the latter, a hemp CBD brand, on what he’d learned about organic ingredients. Organic is a nice match for hemp CBD, but it’s not happening with enough farmers and enough brands, he says. “Ninety-nine percent of the farm acres in America are not organic, and that’s where the vast majority of industrial hemp is being grown,” he says.

If it were happening more widely, he believes, organic hemp could keep the dietary supplement branch of the hemp supply chain rooted in family farms. But he sees little evidence that the fast-growing category is committed to organic standards. “Did you know that the vast majority of every hemp CBD brand is using Monsanto Roundup corn ethanol to process their CBD?” Roulac asks.

In that sense, the natural products industry, and the supplement industry in particular, is failing to stand up for farmers, Roulac says. “The natural food industry has given a hall pass to the CBD industry,” he says, explaining that there’s no paperwork or certification behind most organic claims for hemp. Organic certification wasn’t possible before the 2018 Farm Bill was passed and is still being worked out now.

Gone to seed

Whether hemp farmers need help to come from the natural products industry or not, they certainly need help, says Jeffrey McConnaughey, who, until early July, ran a hemp growing operation for the Rodale Institute to research how organic farming techniques could best be applied to the crop. Practices and techniques for growing hemp organically are not well established, and the genetics that would allow it to grow organically in different climates and latitudes have not been developed, McConnaughey says.

Without that support, small farmers may find themselves outgunned. First-mover status doesn’t mean much if the numbers don’t add up. “As the prices continue to fall, it’s not going to be economical for the smaller farms,” McConnaughey says.

As research is conducted, however, it may be that the advantages the big seed companies have in producing hybridized varieties of other crops that grow well in varied climates and locations may be lacking for hemp. Hemp genetics may favor regional varietals that make the Big-Ag one-seed-fits-all model impractical. That could give small farms a better chance and yet still not be enough, says McConnaughey.

Outside of select niches, the realities of agricultural economics favor big farms with big capital, he says. Hemp could thrive as a niche market the way organic vegetable farms can turn a profit when they’re close enough to big cities to make the farmers market and gourmet restaurant trade work. But he’s not sure he sees hemp as a niche crop in the same way an heirloom tomato catches the attention of a farmers market shopper. “Honestly, a lot of the stuff I’ve seen, I wouldn’t call niche market,” he says, explaining that when CBD is available at gas station convenience stores, it can be hard to elevate to single-vineyard status.

The good news, McConnaughey says, is that at least some of the equipment and infrastructure farmers use to grow hemp could grow those tomatoes too. Hemp could be the first step in a longer plan, he says. “If these farmers are able to be adaptable enough, they can kind of jump into hemp while the prices are high, and then maybe transition into different crops other than just corn and soy.”

Placing bets, taking risks

For McKay, farming has always been a matter of taking risks and placing bets. He was around for a hops boom sparked by the craft brewing market and saw some of his fellow farmers take too many risks before prices settled.

He’s not sure how many of the newer hemp farmers can claim a similar perspective. “They’ve probably got capital behind them,” he says, “but put somebody else’s money with somebody who’s never done it before and it’s like you’re lining up for disaster.

“You gamble on something you know nothing about.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like