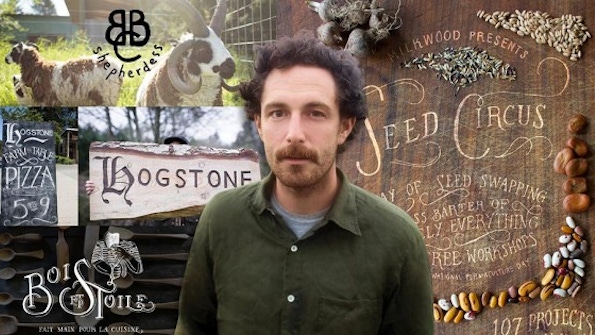

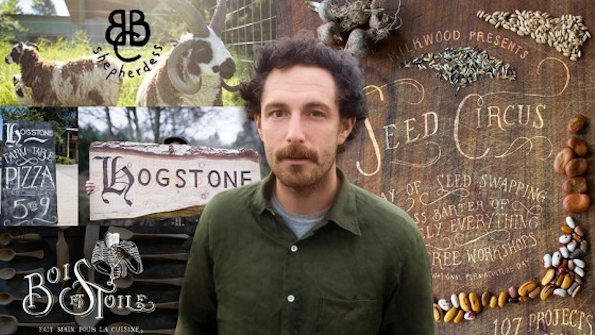

Marketing the farming lifestyle: Under the auspices of his Farmrun studio, Plotsky serves as a one-man agency for the America of dirt roads and muddy work boots.

July 16, 2014

It’s a story as old as America itself. Young man enters the ivy-covered halls of a venerable northeastern college with no great plan. He emerges four years later with a degree and a clarion call only he can hear beckoning him toward a journey deep into America’s back roads to reconnect with a natural order that society seems to have lost along the way.

It’s a story as old as America itself. Young man enters the ivy-covered halls of a venerable northeastern college with no great plan. He emerges four years later with a degree and a clarion call only he can hear beckoning him toward a journey deep into America’s back roads to reconnect with a natural order that society seems to have lost along the way.

Marketing the farming lifestyle via @naturalvitality @newhope360

Although his run was cut short early, the initial experience meeting farmers ultimately led him to relocate to rural Washington State, where his passion for documenting American agrarian enterprise has evolved into a professional calling.It’s a journey of rediscovery that retraces the footsteps of so many American thinkers, from Emerson to Whitman to Thoreau. Sometimes it works out right, as in the case of Andrew Plotsky, a twenty-six-year-old native of Washington, DC, with grand plans upon his graduation from Skidmore College in Upstate New York to run the length of America on foot, pushing his belongings in a baby jogger, intending to document small farms along the way.

It turns out that there are a burgeoning number of entrepreneurs and craftspeople with valuable products and services to provide, but no one to get their message out. That’s where Plotsky steps in. Under the auspices of his Farmrun studio, Plotsky serves as a one-man marketing agency for the America of dirt roads and muddy work boots.

He does everything from designing logos for fermentation workshops to creating posters for young farmers’ social mixers, to implementing a marketing campaign for a farm-to-table pizzeria. Then there are the videos, like the one about an old man named George who still makes boots by hand, or the twelve-year-old boy, Henry Miller, who fletches his own arrows, hunts and skins his own game, and makes the skins into clothes.

This was a career outcome Plotsky could scarcely have imagined when he was growing up as a third-generation East Coast urbanite in the nation’s capital.

Beginnings

“I was a pretty apathetic teenager. I didn’t have a very wide view of the world at all when I went away to college,” Plotsky tells Organic Connections. “I was good at my high school science classes and had taken a liking to biology. So I went off just kind of accepting that I would major in biology when I got to Skidmore.

“Those first two years I was a lot more interested in socializing, which was nice, but that started to change about halfway through my college career when I switched majors to environmental science. That was really the beginning of my interest in agriculture, and also when I began to develop the tools of self-expression and design that I use now.”

Taking advantage of his college’s liberal arts platform, Plotsky was able to shape a couple of his own classes to encompass his growing interest in photography, and even to create a televised cooking show for a semester. “I featured a different local farmer in each episode,” Plotsky recalls. “I talked to them about political issues pertaining to the food system; then I took their food into the kitchen and made a meal using just the stovetop, standing in front of the camera in a totally Food Network–style format, cooking the meal and talking about food politics.

“It’s horribly embarrassing,” Plotsky quickly adds, laughing. “I’m actually surprised I just told you about it, because I don’t ever want anyone to see those videos again. I joke with people that I’ll have a grand ‘re-premier’ once I win an Academy Award or something like that.”

Plotsky can afford to laugh at his rookie efforts now, but he also credits his current level of success to a decision he made early on to just stop caring what other people might think about his creative projects. “A pretty common mindset for people who are starting out in a new medium is to worry whether their work is good or not good and let that inhibit them from continuing. I just didn’t care, and that allowed me to actively practice and gain more experience in photography, video, illustrating and lettering, and enabled me to get better at these things over time. Each successive poster that I made and each successive set of photographs got a little bit less bad.

“I’ve had very few, if any, aha moments in my life,” Plotsky summarizes. “Most things happened slowly.”

Farmrun

During that same college period, Plotsky began to run. “Running seemed integral to the food, health and environmental ethos I was developing. Then, when I graduated, I was just desperate for more interaction with sustainable and small farmers. There was so much that excited me about their practices and culture, but I knew so little about it. I just wanted to see what was out there.

“I had done a bit of international traveling before, and had come to the conclusion that I’m less interested in going overseas when we have this huge, beautiful country full of really interesting people. I wanted to simultaneously discover the US and meet some of these folks.

“So, naturally, I decided I would put all my belongings in a baby jogger, bring my camera, because I was into photography, and run across the country,” Plotsky says with a hint of a chuckle.

“I had started writing as well by that point. I was very inspired by David Sedaris and Tom Robbins—Robbins more stylistically and David Sedaris more for the short-format first-person essays that he writes.

“The plan was to find interesting farmers, run to their farms, hang out, work with them for a couple of days, get to know them, take pictures, and then write stories about them

The plan was to find interesting farmers, run to their farms, hang out, work with them for a couple of days, get to know them, take pictures, and then write stories about them.” The photos and essays were to be posted in a blog Plotsky had begun calledFarmrun.

“I got the baby jogger,” Plotsky continues. “I had just run a marathon a couple of months before, so I was in good shape and all ready to go. I started in Provincetown, Massachusetts, which is right on the tip of Cape Cod, and ran down to Chatham, at the bottom of the Cape. Then I was offered a job, and so I aborted.” For Plotsky, the immediate sense of reward and satisfaction gained from a hard day’s work at a job made the idea of running for running’s sake suddenly seem superfluous.

But the agrarian seed was planted and Plotsky did cross the country after all. In 2011 he moved to Vashon Island in Washington State, where he spent three years learning the craft of meatsmithing under the tutelage of a young farmer–mobile butcher named Brandon Sheard.

All the while, Plotsky kept on creating his videos, posters and photo essays about agrarian enterprise. The Farmrun blog he started back East evolved into Plotsky’s current business; and the homepage of his website, Farmrun, now serves as the storefront for his “agrarian creative studio,” which still maintains a blog documenting his ongoing experiences.

Though Plotsky’s work and his writings conjure up adjectives like spiritual and earthy, he has little interest in being lumped in with the modern-day hippie. “When I hear the word hippie, it implies a lot of mental effort in thinking about possibilities and not a lot of action,” Plotsky explains. “Whether it’s the philosophy or the substances that people partake of that dissuade activity, I have always been interested in folks who are more active.”

Video acclaim

While signs and logos give one a sense of Plotsky’s talent to capture the agrarian spirit, his videos allow viewers to get to know these individuals. Plotsky’s five-minute video “George’s Boots” profiles George Ziermann, an Oregonian bootmaker who has been making his own boots by hand for decades. Ziermann is getting on in years and looking for someone to take over his otherwise thriving business, but he is having no luck, lamenting that there are no younger local people left who possess the classic American work ethic.

“The impetus of that video is that I wanted to help George find someone to buy his business, because he is entirely unfamiliar with today’s technological methods. He doesn’t own a computer. He doesn’t know how to use the Internet.”

The video short created a small sensation in certain Internet communities, and Plotsky has some thoughts as to why. “George is an incredible craftsman and a very romantic icon for our time because he is a self-made success story. He is an old guy who has lived through a lot of rough periods of our history under tough circumstances, engaging exclusively in trades that are based on manual labor.”

But Plotsky is also a bit circumspect about the popularity of “George’s Boots,” noting, “People like watching other people work and then seeing the product of that labor when it’s presented in a polished video. But when it comes down to it, they’re not that interested in devoting the rest of their lives to mastering a single task like George has.”

Yet the net result seems to be positive. “I have gotten an incredible response to that video, and so has George. He’s had phone calls from all over the world, and received visits from six or seven people.” Because of Farmrun, Ziermann’s bootmaking shop may just have an heir after all.

Finding the right balance

Today Plotsky and his partner live on the Columbia River, where they grow salad greens and diversified vegetables and intend to form a CSA partnership in addition to maintaining Farmrun. They’re two widely divergent enterprises that demand he embrace both technology and dirt.

“I don’t spend all that much time on Twitter or Facebook just doodling around for my own enjoyment,” says Plotsky, describing how the Internet impacts his life; “but if I’m trying to get a bunch of people to see a new video or logo I’ve made, I’ll put that stuff up there.”

Plotsky adds, “We live in the time that we live in, and I don’t want to denigrate myself by presenting myself as cut off from the mainstream just to fit the image of being agrarian.

“I think that there is a pervasive idea about land-based workers being Luddites,” he concludes. “A big point of Farmrun is to help bridge the gap between people who are literate on the computer and people who are literate in the land, and to create cultural value for the land folks.”

You May Also Like