In 1994, the U.S. dietary supplements market underwent a seismic shift in its regulatory model when Congress passed the Dietary Supplements Health and Education Act. Because supplements were regulated as foods and not drugs, the industry was liberated to freely market and innovate. The attendant presumption of safety meant the burden of proof fell on the FDA to pull any unsafe products from shelves after they were already there. This is counter to the rest of the world’s regulatory models, which feature pre-market approval by regulatory bodies before supplements are allowed on the market. The boom time in the U.S. market began before the ink was dried on the legislation.

If anyone was in a position to take advantage of the new legal framework around supplements, it was Mark LeDoux. He ran a 37,000-square foot manufacturing facility called Natural Alternatives International and had sat on the Council for Responsible Nutrition’s working group that provided part of the template for DSHEA. Yet with an inside track to profiting in the DSHEA era in the U.S., LeDoux instead decided to look past it all and hold himself to the much stricter requirements of Australia’s notorious heavy-handed Therapeutic Goods Administration.

“The sign outside my door says ‘International,’” LeDoux explains. “We were focused on not just the U.S. market but also expanding the business internationally. One quick way to do that is to go through the TGA. It allowed me to access 47 markets around the world. Very few U.S. producers have it. Even though it’s expensive, in the grand scheme of things it’s a huge differentiator.

“It’s no small undertaking. The process is labor- and capital-intensive. The first time we initiated the audit process,  I believe it took about four days of audits and an ensuing three months of planning and facility and system modifications to achieve success as a TGA-certified facility. I daresay, very few companies in our industry know what an air shower is, much less have one deployed in their operating facilities.”

I believe it took about four days of audits and an ensuing three months of planning and facility and system modifications to achieve success as a TGA-certified facility. I daresay, very few companies in our industry know what an air shower is, much less have one deployed in their operating facilities.”

LeDoux says he spends half a million every year maintaining his TGA certification. But it’s hardly held the company back. Today, NAI has a 200,000-square-foot plant in California and a smaller office in Switzerland, and half of its business is abroad. The company is a leader in Prop. 65 issues around heavy metal testing, can do organic, and spends north of $2 million a year on QA/QC alone. The firm also has its own in-house testing labs with the full range of equipment, from microscopy to HPTLC. NAI’s entire U.S. operations are TGA-certified, including its raw material receiving; warehousing; internal laboratories; blending; powder processing and packaging; tablet compression and coating; encapsulation; and consumer packaging systems.

TGA, what a world-class regulator looks like

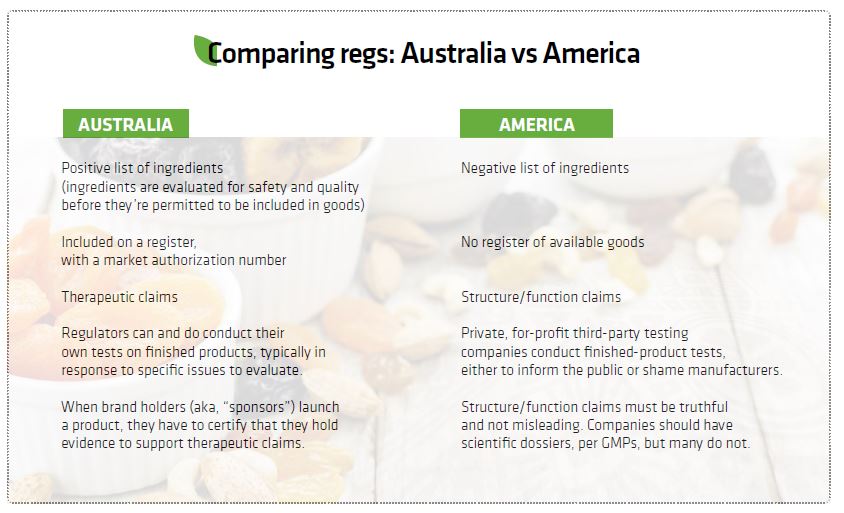

The Australian standards are substantial. Top-line regs include pre-market notification of everything from product launch to advertisements, strictly audited GMPs, a tightly controlled positive list of approved ingredients and post-market surveillance. But it’s the expertise of the enforcement agents that really makes TGA rise to the top. The industry legend is that you’d rather have FDA GMP auditors living in your office for a year rather than have TGA agents audit your facility for four days.

The Australian regulatory structure views dietary supplements as “complementary medicines.” More than 1,600 new complementary medicines are listed every year, each one subject to pre-market approval by the regulatory agency.

Industry killer? Well, Australians spent $2 billion in out-of-pocket expenses on complementary medicines in 2011—and only $1.6 billion on pharmaceuticals. Sales of vitamins and supplements will overtake OTC medicines in 2015 for the first time, according to estimates by Euromonitor.

“It would have to be assumed that the role the TGA plays in regulating these products is a key component in ensuring consumer confidence,” says Steve Scarff, director of regulatory and scientific affairs at the Australian Self Medication Industry, a trade group representing OTC and complementary medicine companies.

While technically operating under a pre-market approval scheme, the TGA separates supplements into “listed” and “registered” categories. Registered products—examples include glucosamine and Ester-C—are able to carry bonus health indications that listed ones cannot. The vast majority of supplements are merely listed, because they are considered to be of relatively low risk to consumers—essentially equivalent to GRAS. However, even this permitted list of ingredients is “quite restricted,” according to an executive at a major Australian supplement brand. This is mostly because having a new ingredient evaluated by TGA is time consuming and expensive, and no intellectual property protections are granted. Two years and $100k later, and your competitor can say, “Thanks, and here’s my me-too.”

“The Australian industry accepts that the higher standards imposed on us will lead to a higher cost base,” says Carl Gibson, CEO of Complementary Medicines Australia, an association of stakeholder groups including suppliers, manufacturers, retailers, MLMs and consumers. “But we believe consumers understand that quality is worth paying for. Our current beef is that there is no intellectual protection for a large proportion of complementary medicines regulated by the TGA, which creates a disincentive to innovate or bring new products to market.”

TGA’s annual audits strictly enforce GMPs on aspects of manufacture including raw materials, excipients, dosage, testing, labeling and packaging. “A manufacturer of complementary medicines is required to be licensed for all steps of manufacture, including testing, dosage form manufacture, packaging and labeling,” Scarff says. “This requires inspection by the TGA and a license to be issued before products can legally be supplied on the Australian market.”

The TGA holds manufacturers to the Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme (PIC/S) standard of GMP. TGA has mutual recognition arrangements with regulators of different countries that operate under similar PIC/S GMP standards. While TGA certification does not give carte blanche to markets in other countries, the PIC/S standard means a manufacturer has to go through a paper application process that takes a few weeks, rather than a significantly more time-consuming and burdensome full site inspection process.

“The Australian evaluation process and manufacturing standards are typically viewed quite highly in other jurisdictions,” says Scarff, “This may simplify pathways to importing and selling Australian complementary medicines. However, other countries will have their own specific requirements surrounding ingredients and dosages, labeling and claims, so products that are approved for supply in Australia may not necessarily be compliant with the requirements for those countries.”

Even so, LeDoux said it was the right call to get TGA certified and take his quality-stamped products around the world instead of hiring 47 sales agents in 47 different countries.

Under the TGA system, no products may be sold without TGA pre-approval, and brand holders have to certify when they launch a product that they hold evidence to support the claims. This is tested post-market by the TGA.

As in the U.S. system, no drug claims are allowed. Although Australian claims are called “therapeutic,” they differ little from American structure/function. For example, a calcium/vitamin D supplement claim in Australia is, “Calcium with vitamin D to help maintain healthy bones, bone density and muscles.” In America, a structure/function claim might read, “Calcium builds strong bones. Vitamin D helps contribute to bone health.”

“Australia has a strong regulatory system,” Scarff says. “This ensures that complementary medicines adhere to stringent principles of quality and safety, confirming that the ingredients claimed to be in products are actually included, and that testing for contaminants and toxins confirm that purity specifications are achieved.”

The best there is—but perhaps not perfect

Even with a zipped-up regulatory model, TGA is not afraid to change regulations based on shifting circumstances. In 1999, TGA added new regulatory provisions that, among other things, required pre-approval of advertisements in print or broadcast media. Loophole: TV infomercials and Internet ads do not receive pre-approval (though they are still subject to the same restrictions on advertising to consumers).

Marketing products on the Internet represents an additional loophole for consumers. That’s because global mail and the web are beyond the reach of the TGA, so consumers can access products that are not necessarily TGA-certified.

Apart from these considerations, a nagging question remains related to the very same issue that dogs the supplements market in the United States—ingredient quality. In a global supply market, with questionable material being produced around the world, can’t unscrupulous manufacturers acquire cheap material?

“Global supply pathways are always going to provide their own unique sets of challenges,” says Scarff. “The advantage of the positive list of ingredients utilized in Australia is that quality standards are specified from the outset, so any raw material supplier, regardless of where they are globally, must supply materials that adhere to these standards.”

In addition, manufacturers must have strict testing protocols in place that confirm the quality and identity of these materials or they risk losing their manufacturing license. Like in the US, the onus lies with manufacturers to remain GMP-compliant, although third-party testing labs also are required to be licensed by TGA.

“I do not believe that the TGA is specifically validating individual test results, but they do audit manufacturers on a one- to three-year cycle, and they will be reviewing in detail both the processes that the manufacturer operates and their test results,” says a major Australian brand exec who requested anonymity. “My sense is that it would be difficult for a manufacturer to consistently forge C of A’s in this environment.”

Seeing a hole in the regulations on the supply side, in 2012 the two leading trade organizations, ASMI and SMA, launched a Good Supplier Practice guideline to provide transparency of the expected standard of quality management for local agents and suppliers, along with a Vendor Qualification Questionnaire. Gibson says the guidelines are “strictly enforced” by the trades.

Can a TGA system renew confidence in the US system?

The dietary supplements industry in the U.S. today is at a bit of a crossroads—born of being in the crosshairs. Consumer confidence in supplement quality is at historic lows, and nobody seems to have answers. Some of the leading metrics for the collapse of consumer trust include:

Third-party groups like ConsumerLab and Consumer Reports test products from store shelves and the score is never 100 percent satisfactory.

The New York Attorney General’s kangaroo court nevertheless did significant and, perhaps, lasting damage to consumer confidence that what’s listed on the label is in the bottle.

The New York Times, which leads media coverage throughout the country, always comes down on the side of more rigorous regulations no matter the industry, and it has never been a fan of supplements. It has made hay aplenty from the New York attorney general’s ham-handed sting operation.

Yes, DNA barcode testing is inappropriate for botanical extracts, but let’s just call that the wrong weapon for the right war. Three of the leading botanical organizations—American Botanical Council, American Herbal Pharmacopoeia and the University of Mississippi’s National Center for Natural Products Research—have established a Botanical Adulterants Program for a reason. Identity and quality issues around botanicals is a significant issue.

The FDA issues 483s and more damning Warning Letters on a weekly basis to companies not complying with aspects of GMPs—and while some are minor, like not having written SOPs, on occasion they reflect practices that give no thought to product quality.

Sports supplements and weight-loss pills are adulterated with pharmaceuticals so often that it sometimes seems like the only thing keeping those sectors going are consumer ignorance of the problem and a greater dollop of hope that a miracle pill will solve their vanity issues.

Fly-by-night, internet-only supplements of questionable veracity are easily available, and nobody seems to be able to do anything about it.

“Give me a break,” LeDoux says. “I’ve been at this 35 years. I’m getting tired of seeing these products sold on late-night TV with these potentially fatal combinations of drugs masquerading as supplements. America is the only country that doesn’t require pre-market registration. Every other market I sell into, whether it’s Russia, the Middle East, Scandinavia, pick it, you have to tell people, ‘Here’s what I’m selling, here’s what’s in it, here’s where it’s made,’ and then they give you a document that says ‘good to go’ and you sell it.

“The concept of pre-market notification and listing in Australia is something I think we would do well to adopt in the U.S. The industry needs to clean up its act. Perception becomes reality quickly.”

Whoa, Nellie! You mention “pre-market approval” to the U.S. supplements industry and you can see hackles being raised from a mile away.

“Our critics seem to go straight to pre-market approval as the answer in search of a problem,” says Steve Mister, president and CEO of the Council for Responsible Nutrition.

Mister says that while the stricter regulatory models of Canada and Australia have their benefits, the burden is too great when considering costs to register products and the lag time between filing and approval. As noted earlier, registering a new ingredient in Australia can take 18 months to two years and cost perhaps $100,000. (Tellingly, under the still-pending New Dietary Ingredient rule in the US, the cost of successfully filing an NDI—even a lesser GRAS dossier—can cost in the high five figures and take several months. And most NDIs are rejected by the FDA.)

“That Australian kind of model is a substantial burden on the legitimate industry,” says Marc Ullman of the New York law firm Ullman, Shapiro & Ullman, “especially for small companies that want to comply and are trying to comply. Before we create a significant change in the model and impose significant layers of new regulation, I’d like to see some real enforcement of the law as written. The problem we’re confronting is grounded more in the presence of scofflaws in the industry. These people are not in the dietary supplements business, they’re in the fraud business.”

For all the work companies do to abide by GMP regulations, the scuttlebutt is that FDA agents are pikers when compared to professional career regulators Down Under. Ullman says this is because supplements get little respect—and littler funding—within the FDA.

Ullman says it would make a difference merely to elevate the Division of Dietary Supplements to an Office of Dietary Supplements. “That makes them a line item in the budget, and with that comes real accountability. Improvements in the quality of inspections and enforcement go hand in hand with holding the FDA accountable for what they do with supplements. And that is tied in to elevating the Division of Dietary Supplements to an Office of Dietary Supplements.”

That might sound like semantics, but the FDA’s division employs 25 people. They are both stretched thin and not given a great deal of respect within the federal government. For example, Ullman says, division investigators do not specialize in supplements, and the Department of Justice shows little enthusiasm for going after dietary supplement cheats.

“I don’t think the scofflaws are going to start paying attention as long as the consequence is a letter,” Ullman says. “Companies that get 483s or warning letters play it out. Kabco was in business three years from the first warning letter to an injunction. That’s three years of non-compliance. There’s no real risk for those people.”

So, more money for the FDA, and more aggressive prosecution of scofflaws. Raise your hand if you think either of these are likely to come to pass. That leaves the industry in the uncomfortable position of passively accepting cheaters and thieves who are shaking the foundation of the larger responsible industry, or having to swallow inelegant sledgehammer legislation that gives up and calls for pre-market approval. Surely there’s a sensible middle ground, but good luck finding sensible people in Congress anymore.

LeDoux thinks attitudes in Congress are shifting, as they are in the culture. Millennials are demanding transparent business practices and quality goods. There’s enough quality supplement makers that would actually benefit if substandard players were shown the door, even if an increased suite of regulations make the cost of doing business go up and slow down.

“Pharma is a big player in this space. Frankly, they would not have any heartburn with any of these concepts,” says LeDoux. “The good guys stay, the bad guys find a new line of work, and consumers win.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like