March 15, 2017

The questions keep coming up in the controversial corners of sports nutrition and weight loss. Is this new stimulant safe or not? Is it a constituent of this exotic plant or not? If so, does that make it legal? What if it’s isolated and synthesized? And there’s a larger, unspoken question hanging over all the others—Is this particular company a good actor or bad actor? Anyone selling to the fringes of bodybuilding culture has to be doing something wrong, right?

We’ve read these stories before, some in the pages of this journal, but this article does not seek to tell one of those stories. This article takes an intentional pass on matters of legality surrounding DMAA or BMPEA, and another pass on whether a company like Hi-Tech Pharmaceuticals is “good” or “bad” for the industry. In the wake of Hi-Tech’s defamation lawsuit against Dr. Pieter Cohen, NBJ would rather pause, assess the ramifications to industry of that singular event, and then add a new question to the mix. Who’s going to sue next?

Setting the stage

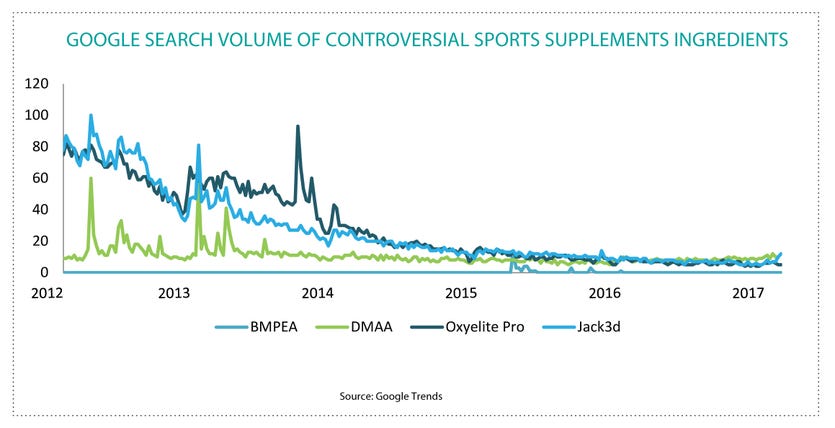

Hi-Tech Pharmaceuticals, a supplement manufacturer out of Norcross, Georgia, is not afraid of a lawsuit. The company operates in polarizing categories with products catering to weight loss, muscle building, and sexual enhancement. Hi-Tech has been on the receiving end of warning letters related to the controversial ingredient BMPEA and enforcement actions for DMAA. In turn, the company has mounted legal defenses in support of both ingredients, and that’s just scratching the surface.

“We’re willing to do this to fight for our business and our industry,” says Jared Wheat, Hi-Tech’s CEO. “We challenged Ron Kramer and ThermoLife on L-arginine. They sued 81 people and only three got to trial. We fought with VPX Sports and GNC to overturn those patents and invalidate those claims. Just last week, we were awarded $950,000 in legal fees in San Diego. That’s a real deterrent to the patent trolls.”

And on another front: “We’re suing FDA over DMAA, too,” says Wheat. “We’ve finished all the briefings and now it’s in a judge’s hands. Our claim is that DMAA is in geranium, and that FDA is acting arbitrarily and capriciously with these warning letters. You’re supposed to ban ingredients through Congress, not with warning letters. That’s how DSHEA was written.” According to Wheat, Hi-Tech has spent over $2 million to date litigating DMAA.

And there’s more: “A lot of people don’t push back,” says Wheat. “We’re one of the few saying we’re not going away. We responded to FDA on BMPEA with three-ring binders full of support and got no response back at all for 18 months.” It’s this particular ingredient, BMPEA, that brought Harvard into the mix.

Dr. Pieter Cohen is a Harvard researcher, and, often, an outspoken industry critic with high profile in the mainstream media. In April 2015, he and some colleagues published research on the presence of BMPEA in off-the-shelf dietary supplements, including Hi-Tech’s Black Widow and Fastin-XR. After the ensuing press and warning letters from FDA, Hi-Tech would file suit against Cohen in Georgia, seeking $200 million in damages for libel and slander, only to see that case dismissed and subsequently refiled in Massachusetts at smaller demands. That case went to trial in October 2016, and was ultimately decided in Dr. Cohen’s favor, but not before causing slow-simmering shock waves across the industry and among advocates of free speech and unfettered scientific inquiry.

“I will say that it’s not surprising this happened to Dr. Cohen,” says Anthony Almada, founder and CEO of Vitargo Global Sciences. “He’s a vociferous critic, and sooner or later, industry fights back. But this has never happened to this degree in the nutrition industry, not that I can recall. Many have criticized the critics, but never to the extreme of litigation leveled at specific individuals over their opinions or data.”

While the Council for Responsible Nutrition refrains from commenting on specific companies, President and CEO Steve Mister does offer the following perspective: “We don’t agree with everything Pieter Cohen says about public policy, but he is doing important work with products in the marketplace that aren’t safe for consumers. I’ve seen this particular case portrayed as a larger struggle to fight back against overreach at the agency, and if that’s the intent, that’s truly unfortunate. We should not be discouraging legitimate scientists from investigating our products. We should be inviting and encouraging independent academics and researchers to put us under some scrutiny. At a time when the industry is focused on being more transparent and inviting accountability, this seems to be moving in the opposite direction.”

Lesson #1: NDIs

In talking with experts to best contextualize the long-term impact of Hi-Tech v. Cohen, three lessons came into focus. The first would have to be some honest assessment of the complexities involved in natural products science, and the frustrations of living with NDIs as a vagary of DSHEA.

“Just because a researcher didn’t find BMPEA in Acacia rigidula, don’t stop there and take that at face value,” says Wheat. “You dig and it’s not an ‘FDA study’, it’s a study done by some junior FDA employee on the side. If you don’t preserve the alkaloids when you pluck the plant, then they die. Texas A&M used argon blankets to protect the plant until they could test it, and they found BMPEA in there.” Most every controversial stimulant that’s made a headline, from DMAA and geranium to DMBA and Pouchong tea, carries this kind of uncertain botanical pedigree.

“If you find something that doesn’t occur in a plant, okay, fine, but does that mean it’s not safe?” says Almada. “That’s a different discussion. Presence or absence of the constituent in nature is mostly about chemistry, and sometimes these researchers have to venture off that island into biology to address safety. That’s far trickier, and it’s also far more relevant, frankly.” So the chemistry is complex, and the biology too.

But does it even really matter? Without the colorful arguments of lawyers massaging DSHEA into unusual new shapes and purposes, the clear eye of the law could—could—better indicate the requirement of a filing full stop. Some see the matter with this kind of clarity already. “All of these ingredients—DMAA, BMPEA, DMBA, or whatever the next iteration of these stimulants might be—they’re all new ingredients,” says Mister. “This is a fundamental problem. Companies are putting ingredients into the marketplace that are new. They don’t tell FDA, they don’t do the safety studies, and the statute requires it.”

The lesson could be “file the NDI,” but many are waiting to see how the new guidance shakes out. At present, synthetic botanicals are prohibited, a problem for many ingredients in the sports nutrition and weight loss categories.

Lesson #2: FDA

While it’s easy to cast aspersions on the regulators, NBJ found clear criticisms of FDA on several fronts in reporting this article. To begin, there’s that long-standing reputational bias against the industry that colors every move the agency makes. “There are two sides to every story,” says Gene Grabowski, partner at kglobal, a Washington communications firm. “I have clients in supplements and homeopathics, and I can respect and appreciate the need for firm and appropriate regulation under DSHEA. But I also know there is bias inside FDA against these products. There is a very clear bias, even condescension among many people inside FDA and inside the scientific community with very little allowance for alternative forms of medicine, or anything beyond allopathy.”

There’s also tension around the role of the warning letter, and the lack of enforcement to follow. “Warning letters are only as good as your willingness to follow through on them, and FDA is generally not willing to do that,” says Todd Harrison, partner at Venable. “That makes you think, as a lawyer, that FDA may not be as confident in its position as one would think. Thus, it sows seeds of doubt in the industry regarding FDA’s position on the regulatory status of certain ingredients.”

Wheat takes it a few steps farther, saying: “FDA has basically taken a position that they’re going to regulate by warning letter, at least they did under the Obama administration. I’ve been doing this for 20 years and no prior administration had acted that way. It’s as if they expect to write a warning letter and everyone will go away, whether they’re right or wrong. There are specific ways to get product off market spelled out in DSHEA, and they try to do it faster. Then, when somebody sues for violation of the Administrative Procedure Act, FDA turns around and says a warning letter is not final agency action, so you can’t sue us. It’s a chess move. They didn’t expect somebody to stand up.”

A common desire unites this hand-wringing over the squiggliness of scientific proof and fickleness of FDA’s backbone—clarity from the agency over the questions that began this article, questions increasingly brought to the fore by controversial players like Hi-Tech. If there are legitimate questions about DMAA and BMPEA as dietary ingredients, then there are questions about the need for filings. There are questions about the status of synthetic botanical constituents, and about grandfathering isolated constituents from grandfathered ingredients. As Harrison puts it, “Regardless of the course of action taken, there needs to be clarity around these issues, and there is simply no clarity at this point.”

Lesson #3: The Trump factor

A final lesson from the legal dramas brought to light by Hi-Tech concern President Trump and the new administration. “One of the things we’re seeing here in DC already is trade associations and corporations holding back on spending,” says Grabowski. “It’s a wait-and-see approach with the new administration with many working under an assumption that regulations are going to be rolled back and they won’t need to spend as much. But the real careerists at EPA and FDA are trying to get their licks in now, before the rollbacks, if they can.”

This speaks to a growing consensus of voices predicting even less effective enforcement protocol coming out of FDA. “I fear we are going backwards over the next four years,” says Harrison, “and this is a double-edged sword for industry. States like New York and California will be more than willing to step into that vacuum at the federal level and take legal action against ingredients that may have questionable regulatory status.”

So if not Washington, DC, then the states, and if not the states, then the CEOs. “I think you’re going to see, in general, more lawsuits from entrepreneurial CEOs, many of whom are company founders who don’t have the checks and balances of a strong board,” says Grabowski. “So privately-held companies, mid-caps, and organizations led by headstrong CEOs who feel they’re been wronged. You’ll almost certainly see more lawsuits. Donald Trump has changed the tenor of things. He’s made it okay to file lawsuits like this [Hi-Tech vs. Cohen], almost like it’s more in style now.”

While it may be condoned at the highest levels, defamation litigation is still a tough charge to make stick. “Filing a lawsuit can be a double-edged weapon,” says Grabowski. “People who have deep pockets tend to use it more than those who don’t. Look at President Trump. He has used litigation and very public attacks to great effect, but there’s only one Donald Trump. Most people who try to imitate that style or use those tactics usually end up making expensive mistakes. Filing a defamation lawsuit is a very expensive way to go.” In a time of tumult and swamp-draining, more mistakes will certainly be made.

Much of the reporting around Hi-Tech v. Cohen has taken the stance that litigation of this sort is bullying. It’s a form of harassment that could result in a chilling effect on researchers speaking out. An article in STAT even connects Wheat’s case directly to Trump promising to loosen up defamation laws. “You can loosen libel laws all you want, but you’re still subject to the first amendment,” says Harrison. “It’s not that simple. We should foster free speech. It’s abhorrent to do otherwise, whether that’s through lawyers or violence.”

Wheat would agree. For him, the Cohen suit wasn’t about silencing a critic, it was about demanding scientific rigor. “I’m all for the first amendment, but you have to speak truthfully. I’m not out to chill free speech—just the opposite. If you haven’t noticed, I’m pretty outspoken and believe in my views.”

From Nutrition Business Journal's 2017 Dark issue. Get the full issue in the NBJ store.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like