Much like the organic movement has carved out a dedicated space in many grocery stores, it may next take over its own little corner of a much larger entity—the Internet.

Afilias, the world’s second-largest domain registry, is giving qualified brands, retailers, farmers, restaurants and organizations that focus o n organic the opportunity to register for a website URL that ends in .ORGANIC, instead of the traditional .COM. This is possible thanks to the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), which in February approved 100 new generic top-level domains (TDLs) including dot-organic, dot-careers and—interestingly—dot-ninja.

n organic the opportunity to register for a website URL that ends in .ORGANIC, instead of the traditional .COM. This is possible thanks to the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), which in February approved 100 new generic top-level domains (TDLs) including dot-organic, dot-careers and—interestingly—dot-ninja.

The potential benefits of having a dot-organic website are obvious: It would enforce association of certain brand names with the organic label while also helping consumers identify the “real” organic products on the Internet. But there are logistical concerns: How will the organic TLD be regulated? How much will it cost companies? Will the integrity of organic be preserved?

We went straight to the source and posed these questions to Roland LaPlante, Afilias’ chief marketing officer, and Meg Watt, the brand manager for dot-organic.

NFM: Let’s start by talking briefly about why organic needs its own space on the Internet.

RL: In dot-com, anyone can say they’re organic. They don’t have to show anybody that they’re organic, they don’t have to be vetted or certified or anything. So our thought was that real organic producers were at a disadvantage because the very thing that makes them distinctive in the marketplace is now being made generic.

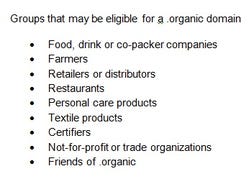

So we said, here’s a new model. We will offer dot-organic names on the Internet, but we will only offer them to legitimate, bonafide, proven members of the organic community. We have a reasonably broad definition of what that is but very specific criteria for each member. We are going to check every single registrant to make sure that these guys actually do have organic credentials.

NFM: What are those criteria?

RL: We’re not defining organic here. All we’re doing is saying that we can see that you have met certification requirements. There are organic certifiers all over the planet that certify entities based on different standards. We’ve identified 57 different standards (used in different parts of the world) and gotten a list of the certifiers for each of those. When an applicant comes to us for a dot-organic name, we will check against the publicly available list of entities that have been certified by these various organizations.

NFM: And you have the manpower to do all of that?

RL: We’ve bu ilt a system that automates at least some of it, but not all of it—recognizing that different organic community members have different things that they bring to the community. For example, if an organic farmer comes to us and asks for a dot-organic domain name, we’re going to be able to pretty quickly and in an automated fashion identify whether the certification number they give to us is actually the real one that matches them. We can check that online. The same goes for organic food and drink and co-packer companies and other ones who can get certified.

ilt a system that automates at least some of it, but not all of it—recognizing that different organic community members have different things that they bring to the community. For example, if an organic farmer comes to us and asks for a dot-organic domain name, we’re going to be able to pretty quickly and in an automated fashion identify whether the certification number they give to us is actually the real one that matches them. We can check that online. The same goes for organic food and drink and co-packer companies and other ones who can get certified.

But there are other categories of registrants—for example, organic restaurants. What we would do in that case is look at their menu and look at their website. If they have one organic chicken dish out of 300 on their menu, they’re not going to make it. If they’re Roland’s Awesome Organic Restaurant and everything in it is organic, they will deserve a dot-organic name. We’ve tried to create decision rules that allow that to be as black-and-white as possible, but we’re going to end up making some close calls here and there. We’re going to try and be conservative.

(Editor’s note: Read the full registration policy here. According to the policy, eligible food or drink companies and farmers must produce at least one certified organic product. Co-packing companies must have at least one packing facility that is certified organic. Restaurants and retailers must either be certified organic or have a section of their website or menu, respectively, dedicated to the certified organic products they offer. Applicants for dot-organic sites have 15 days after application to submit verification of certification, and their sites won’t go live until they’ve been approved.)

NFM: What’s the process of switching over a website after being approved?

RL: The process should take some time. You switch over a part of your website first, so you take your leading new products and put that in a dot-organic. Then over time, maybe a two-year period, you begin migrating the rest of your site over. The reason for that is so that you don’t lose any search engine optimization power. You don’t want to stop using your dot-com, but eventually you’ll end up redirecting your dot-com to the dot-organic, because dot-com doesn’t add anything to your brand name.

NFM: Will there be ongoing regulation as companies onboard their content?

RL: We have an acceptable use policy for dot-organic that allows us to take sites down or take the names away in the event that somebody abuses their privilege and does either non-organic or—heaven forbid—anti-organic activity—on that site. That’s something that every registrant signs on to accept when they apply for the domain. Also, whenever a domain gets transferred from one registrant to another, we’re going to check that the new registrant also meets the criteria.

NFM: What costs will this add?

RL: A domain name is an incidental expense for most businesses. This domain is going to retail in the $70-per-year range. The reason it’s more than a dot-com is because we have to pay for the verification process.

NFM: When will early adopter brands start making that transition?

NFM: When will early adopter brands start making that transition?

MW: Actually some of them have. Applegate, if you go to the dot-com, that’s the company's natural products now. Applegate.organic is the organic products. RodaleInstitute.organic and research.organic are both up. Stonyfield is actually using theirs in an interesting way: Stonyfield.organic is set up for its farmers. Right now it’s set up like a landing page, but Stonyfield plans to put a login site for its organic farmers to use. Bread.organic is currently in use, but you’ll see some good premium names are still available.

NFM: How will you define success moving forward?

RL: We expect this is going to grow slowly over time as companies like Stonyfield and Rodale Institute get their sites out and start doing advertising behind it. Over time, we believe that sites in the dot-organic space will be the place end-customers go for authentic goods and services on the Internet.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.png?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)