May 1, 2015

You can’t turn on the television these days without seeing a story about legalized marijuana and the “ganjapreneurs” who are advancing the nascent US pot industry.

You can’t turn on the television these days without seeing a story about legalized marijuana and the “ganjapreneurs” who are advancing the nascent US pot industry.

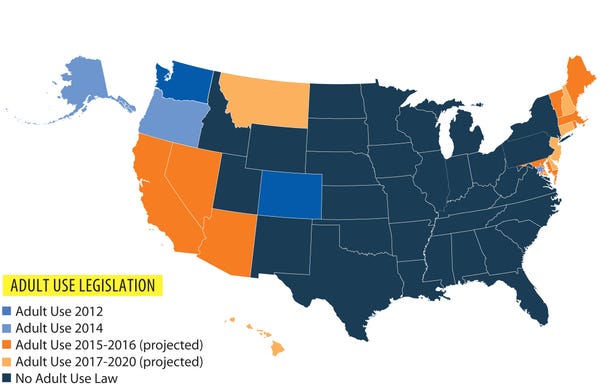

Four states have legalized cannabis for recreational use, and 23 now allow it for medical purposes. Across the country, enterprising pot enthusiasts have baked the plant into almost every food imaginable, synthesized it into ultra-concentrated oils and even mixed it into topical lotions.

Most of this entrepreneurial energy has focused on delivering the plant’s psychoactive chemical, tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC. But a growing number of medical professionals and entrepreneurs are pushing products that contain cannabidiol, or CBD, one of the non-psychoactive chemicals in the plant. There is a growing consensus that CBD holds a variety of therapeutic qualities. Health claims range from reducing seizures in epileptic children and offsetting depression, to improving skin.

These entrepreneurs could be paving the way for the supplement industry’s next billion-dollar market. Before that happens, however, CBD entrepreneurs must overcome a handful of self-imposed hurdles, from unprofessional marketing and shady corporate dealings, to an immature supply chain and political infighting. They must also find a way to win approval of the FDA, which recently deemed the products unfit for sale as dietary supplements.

“The industry is not where we’d ideally like it to be, yet,” says Richard Rose, executive director of the Colorado-based Medical Hemp Association. “We’re seeing a lot of rookie mistakes.”

A History of Legislative Change

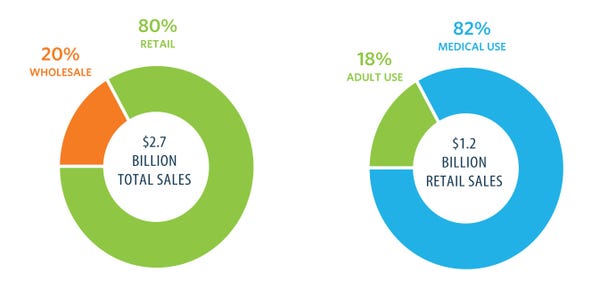

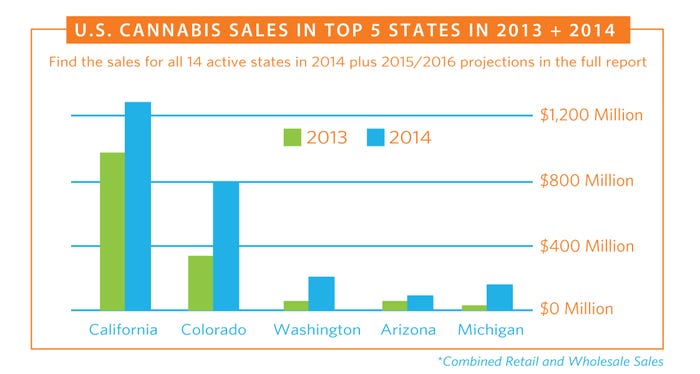

[Charts courtesy ArcView Market Research]

Various federal regulations and statewide bans targeted cannabis through the first decades of the 20th century. In 1942, the final nail was placed in the plant’s coffin when it was removed from the US Pharmacopeia, which effectively erased any therapeutic legitimacy. By the time Congress passed the Controlled Substances Act in 1970—which lumped cannabis alongside heroin, cocaine and methamphetamines—US doctors had long since abandoned cannabis as a mainstream medication.

That’s not to say that individual physicians and cannabis enthusiasts stopped performing their own medical research on the drug. Nobody knows for sure how many individuals smoked cannabis to treat cancer, epilepsy or glaucoma during its prohibition years. Enough at-home research and personal clinical trails went on, however, for hundreds of advocates and doctors to believe in cannabis’ medicinal qualities through the ’80s and ’90s.

A group of early researchers founded the International Cannabinoid Research Society in 1992 in an effort to study the chemicals in cannabis. In 1998, Dr. Geoffrey Guy persuaded the British government to license his company, GW Pharmaceuticals, to develop a cannabis extract for use in clinical trials. After contacting a Dutch seed company, Guy acquired strains of cannabis that were rich in CBD.

In the United States, a seismic shift came in 2004, when the Ninth US Circuit Court of Appeals struck down a DEA regulation to criminalize the possession and manufacturing of oil produced from cannabis varieties that contain very little THC—commonly called “hemp” or “industrial hemp,” because of their use in rope and building material.

Advocates believe the ruling opened the door for entrepreneurs to acquire, possess, and sell hemp products—including oil, paste and seed oil—so long as the hemp contains less than 0.3 percent THC. Since then, entrepreneurs have cited this ruling as the legal umbrella governing the industry.

Entrepreneurs, however, were still forbidden from growing the plant.

Longtime hemp entrepreneur Chris Boucher, vice president of CannaVest, the country’s largest hemp oil importer, says his early hemp oil customers included shampoo companies, independent supplement manufacturers, and even pet food firms. The oil, Boucher says, comes from both the hemp seed, and from essential oils stripped from the stalk of the plant. Boucher says these companies were drawn to hemp oil’s high protein, as well as its perceived health benefits.

Even though these companies complied with the law, Boucher says, they sometimes received letters from the DEA.

“[The DEA] threatened these mom-and-pop vitamin stores for selling hemp seed oil,” Boucher says. “It made no sense. The THC value was like 10 parts per million. There’s more arsenic in your drinking water than that.”

Boucher and other entrepreneurs believe that CBD products are legal, but the rules are still opaque. On May 14, the FDA published its interpretation of the legality of CBD products and said they cannot be sold as supplements. “Based on available evidence, FDA has concluded that cannabidiol products are excluded from the dietary supplement definition,” the announcement said. “FDA also may consult with its federal and state partners in making decisions about whether to initiate a federal enforcement action.”

The Gupta Effect

The CBD industry’s major breakthrough came in 2013, when CNN aired the first installment in a series called “Weed,” starring the network’s medical correspondent, Dr. Sanjay Gupta. The program chronicled the story of Charlotte Figi, a child who suffered from Dravet Syndrome—a form of child epilepsy. It told how Figi’s parents used an extract made from high-CBD cannabis oil to successfully treat the child.

Gupta’s story spurred a series of similar media hits in regional and national newspapers across the country.

CannaVest—which imports raw hemp paste from manufacturers in Eastern Europe, refines it in the United States, and then sells it to various marketing firms across the country—saw its business explode. “Our phones rang off the hook after [Gupta’s] story came out,” Boucher says. “All of a sudden you see these people who are completely against marijuana become completely for CBD oil.”

Boucher says the Gupta report also opened the door for mainstream audiences to read recent studies done on CBD and how the substance interacts with endocannabinoids, which are hormones that occur naturally in the human body. Cannabinoid receptors are actually found throughout the brain, and CBD works through these receptors. A 2012 study in the journal Pharmaceuticals cited 34 different studies on CBD, with 18 of them conducted on clinical populations suffering from schizophrenia, cancer pain, Huntington’s disease, insomnia and other disorders.

“Experimental studies suggest that high-dose CBD may decrease anxiety and increase mental sedation in healthy individuals,” the authors wrote.

Other reports cited CBD as impacting mood, stress and the health of the nervous system. Exactly how CBD impacts receptors to achieve these results is still unknown, as are the long- and short-term benefits of the treatment.

Stuart Tomc, CannaVest’s vice president of human nutrition, says the mainstream attention created a tipping point for CBD products. “It’s the only ingredient where you don’t have to put anything on the label to sell it,” he says. “You just steer them to CNN.”

The New Gold Rush

A quick Google search for the terms “CBD,” “Hemp Oil” and “Hemp Seed Oil” will unearth dozens of oils, pills, tinctures, drops and even chewing gum for sale on respected ecommerce retailers, including Amazon, Etsy and even Ebay. Most of these products have come to market within the last two years, Boucher says.

One recent CBD brand is the Nevada-based Life Enthusiasts, owned by Martin Pytela, a veteran of the aromatherapy market who describes himself as a “healer.” Pytela says he started purchasing wholesale CBD oil and selling it after watching the Gupta report on CNN.

“We started seeing a lot of interest from people with twitches, seizures and wound management,” he says. “The other interest was from the cancer crowd.”

Pytela’s 100-milligram bottles retails for $25 each. He says the margin on his product is approximately 40 to 50 percent, comparable to what he got for aromatherapy products. But unlike with these products, he says, he does not have to advertise the CBD, due to the demand. He takes orders via his website or over the phone, then ships via mail. He says the only hurdles he’s encountered have come from the payment processing service Paypal, which sent him a letter announcing it was terminating his service due to the products he was selling.

Pytela says he’s found ways around Paypal and that CBD is now a major part of his business, accounting for 25 percent of his company’s revenues. That’s up from just 5 percent in 2013. And his total revenues have grown 50 percent since then.

“I could buy a kilo of raw CBD for $60,000 tomorrow and start putting it into my own bottles by the end of the day,” Pytela says. “It is really like the gold rush right now.”

Familiar concerns about label claims and purity

The CBD boom has not been without its problems. A handful of companies drew the ire of the FDA in early 2015, when the agency sent 18 warning letters to seven different firms that sell CBD-based products, telling the companies they needed to stop making health claims in their marketing.

One letter, to the Arizona company CBD Life Holdings LLC, read:

“The therapeutic claims on your website and in promotional literature establish that the product is a drug because it is intended for use in the cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease. As explained further below, introducing or delivering this product for introduction into interstate commerce for such uses violates the Act.”

Of course, these letters are not uncommon in the supplements industry, and numerous start-up companies learn the hard way that they cannot make health claims on packaging or in promotional material. But other letters from the FDA spoke to a more problematic issue: The agency says that it performed tests on the CBD products in question and that at least four showed no CBD.

Another troubling development came in November 2013, when an ex-employee of a prominent CBD manufacturer in Denver took to Facebook and wrote about health concerns in the way CBD is manufactured. The post was eventually taken down, but the employee called the raw CBD material, “crude and dirty hemp paste contaminated with microbial life.”

The developments fueled a schism in the CBD industry between industrial hemp entrepreneurs and the expanding number of state-legal cannabis growers. The latter group, by and large, does not trust industrial hemp, since it is grown in China or Eastern Europe and then transported into the United States. These growers and their patients have circulated literature that claims that CBD from cannabis plants carries greater potency and value than hemp and hemp seed CBD.

“The flood gates have opened, and now all of the CBD comes from hemp, which is an inferior source,” says Constance Finely, owner of Constance Botanical Care in San Francisco. “Hemp has the legal edge, but it’s being pushed by a group of people who are irresponsible.”

But the most damaging development came in November 2014, when a CBD advocacy group commissioned a freelance journalist to produce a 30-page report on the industry. The report, titled Hemp Oil Hustlers, painted a damning picture of the industry as a whole. It highlighted alleged fraudulent corporate dealings by prominent CBD distributors and poked holes in the science behind many of the medical claims associated with CBD. It also provided testing results that showed that some CBD oils contained heavy metals and other contamination.

In the wake of the report, the company Medical Marijuana Inc. launched a $100 million lawsuit against the authors. CannaVest also retested its CBD products alongside the authors, and both groups released a joint statement stating that CannaVest products did not show contamination in follow-up tests.

One of the report’s authors, Martin A. Lee, confirmed the presence of the lawsuit and said, “there is good reason to be cautious” of the CBD industry. Boucher called the report a “hit piece” but admitted it did considerable damage to the industry’s reputation: “When you start talking about heavy metals and contamination, that scares people.”

Where the Future Lies

Whether CBD companies make a push into the mainstream supplement industry is yet to be seen. The industry could likely be shaped by the recent FDA announcement. Whether the agency will pursue any action against CBD companies, however, is unclear. The company HempMeds, owned by Medical Marijuana Inc, displayed its CBD products at the 2015 Natural Products Expo West. Already, a handful of groups have reached out to industry organizations. The American Herbal Products Association has approximately 30 members from the cannabis and CBD space, according to Jane Wilson, AHPA’s director of program development.

AHPA has even produced a modular document of best practices and regulatory advice for how these companies can adhere to local and federal regulations.

“We’re trying to educate a relatively new industry about how to comply with regulations from state to state,” Wilson says. “There are a lot of resources we supply to the conventional supplement industry that apply.”

Other cannabis-specific groups are also working to improve the overall professionalism in CBD. The National Cannabis Industry Association holds regular symposiums where best practices are disseminated. Rose coaches CBD entrepreneurs on what they can and cannot put in their marketing.

A resolution to the CBD problem could be on the horizon. The 2014 US Farm Bill for the first time made a staunch demarcation between industrial hemp and cannabis, which cleared the way for some states to launch pilot research programs into the plant. Kentucky alone will harvest 1,742 acres of hemp in 2015.

The move could be a step toward more government involvement and regulation, which Rose believes is what the industry needs.

“We need to improve the standards for the industry and then promote it,” Rose says. “I came out of retirement for this because you can tell it needs some shepherding.”

Explore these and other trends that are reshaping the supplement landscape in the 2015 NBJ Supplement Business Report.

You May Also Like