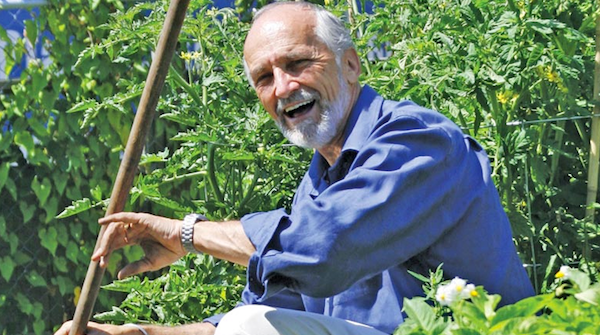

Nature's Path founder Arran Stephens on building an organic business

From his farm-based youth to early organic entrepreneurial efforts, the founder of one of North America's largest organic cereal brands shares his journey to success. Organic Connections magazine reported.

January 28, 2013

Arran Stephens and his wife, Ratana, started Nature’s Path from the back of a restaurant in 1985. The family-owned company is now the largest organic cereal brand in North America, with products sold in 42 countries. Stephens has given giants such as Kellogg’s and General Mills a serious run for their money and is every week besieged with offers to sell out to similar deep-pocket corporate shoppers. As he proclaims far and wide to anyone who asks, that will never happen; for despite his success, it has never been about profit. From the beginning, Stephens has had a spiritual dedication to the organic mission and to creating a company with soul that would carry its integrity intact for generations to come.

Arran Stephens and his wife, Ratana, started Nature’s Path from the back of a restaurant in 1985. The family-owned company is now the largest organic cereal brand in North America, with products sold in 42 countries. Stephens has given giants such as Kellogg’s and General Mills a serious run for their money and is every week besieged with offers to sell out to similar deep-pocket corporate shoppers. As he proclaims far and wide to anyone who asks, that will never happen; for despite his success, it has never been about profit. From the beginning, Stephens has had a spiritual dedication to the organic mission and to creating a company with soul that would carry its integrity intact for generations to come.

“I think we succeeded way beyond our wildest expectations,” Stephens told Organic Connections. “Considering that what we do had the potential of being the norm someday in the world, I wanted to build our company’s base—our strength—so that when the transition inevitably came, we would be strong enough to not get swept off our foundation.”

An organic—and spiritual—journey

Organic production was in Stephens’ blood from day one. “The day I was born, my mom was unloading sacks of potatoes off the back of a truck,” said Stephens. “She was a strong lady. We had a 120-acre farm. Later we moved to another farm where my parents homesteaded, cleared a forest and created an 80-acre beautiful farm on Vancouver Island, British Columbia. It was a real life lesson on the farm, because we used to gather kelp from the ocean in the autumn and spread it on the field; that was our fertilizer. My father extensively mulched and even wrote a little book on it called Sawdust Is My Slave, all about his mulching procedures. When I was a boy he told me, ‘Always leave the soil better than you found it.’ That has become a metaphor for life and a guiding principle that underlies whatever we do at Nature’s Path.”

Not far up the road, Stephens’ life mission was made manifest to him in a pivotal trip to India when he was 23 years old. Of the experience, he told Organic Connections:

There are some of us who are not satisfied with material possessions. I wanted much more out of my life and engaged in a lot of intense spiritual practice of meditation. I had a great teacher named Sant Kirpal [Sant Kirpal Singh Ji Maharaj], and I went and studied with him in India in 1967. He was very well known and respected all over India and throughout the world. He treated me like a son, and I regarded him as my father. I’ve had several great mentors in my life, but he was the first and foremost. The truth is not in India; the truth is not in the Himalayas: the truth is within each one of us. But it requires mentors, I think, to stimulate and awaken that sleeping beauty that’s within all of us. I think each one of us has the capacity or capability to be an instrument. Like Saint Francis said, ‘Let me become a channel of your peace. Where there is darkness, let me bring light. Where there is despair, hope. Where there is sadness, joy.’ I felt that my job, my responsibility, was to act as a transformative catalyst when I got back to Canada.

Upon his arrival home from India, he started right in. “When I returned, I wanted to create a great livelihood,” Stephens continued. “I had $7 to my name and I convinced a couple of people to loan me $1,500. That was starting capital. I bought a failed restaurant and moved the equipment to a location in Vancouver that I thought would be really good and opened this little restaurant. It wasn’t to make money; it was to fill a need. There were no vegetarian restaurants in Vancouver at that time. It was just the right thing at the right place at the right time, and customers began coming in droves. Pretty soon we opened Canada’s first large natural food store.”

The Lifestream lesson

Prior to the success of Nature’s Path, Stephens had another thriving organic products company called Lifestream. “Lifestream was a company that I started in 1971,” he said. “Being undercapitalized I took on a couple of partners over the next three years, and by 1981 it was the largest natural foods company in Canada, and we had some export sales into the United States at the time.”

But a conflict occurred between Stephens and his partners that resulted in the loss of the company. “A partnership problem came about in 1980 or 1981,” Stephens recounted. “It got so bad that it became, ‘You buy me out or I buy you out—it’s not working.’ My partners didn’t have the money to buy me out, and I wanted to buy them out but they wouldn’t sell. So we were at an impasse. I refused to guarantee a loan from the bank until we could resolve this, and it forced the sale of the company in 1981.”

Following that incident, Stephens and his wife continued on their own in Vancouver, operating two natural food restaurants. Four years later, out of the back of one of them, they began the company that would make its mark on the world: Nature’s Path.

Nature’s Path saw unprecedented success, and very interestingly Kraft, the corporation that had purchased Lifestream, one day came back to Stephens.

Fourteen years after I sold Lifestream, we had beaten it in the marketplace with our little Nature’s Path company. I got this call one day from a Kraft lawyer, asking if I would be interested in buying my company back. I looked at it and said, ‘It’s losing money. Why should I buy it back?’ The lawyer then asked if I wouldn’t make an offer. I did so, and they said, ‘It’s worth five times that.’ I said, ‘Well, good luck. Go and sell it.’ Six months later the lawyer returned and said, ‘I’m representing Kraft again, and they’re prepared to accept your offer.’ I said, ‘My offer has just dropped.’ So we actually ended up buying it back for the real estate assets. It didn’t make sense to market two brands, so we folded Lifestream into Nature’s Path and made Nature’s Path a much stronger brand.”

How a small organic business can compete with the big guys?

The odds against his success have never been lost on Stephens—or on his sense of humor.

Not long after we started Nature’s Path, I was at a trade show in California showing some products that we had experimented with. A TV interviewer with cameras in tow was at the show. He was going past us and didn’t even notice our tiny little booth there. So I put the cereal in his face and said, ‘Would you like to see some organic cereal?’ He looked at it and looked at me, and the cameras were suddenly on me, and he asked, ‘How can a little pipsqueak company like you ever hope to survive against the giants of Kellogg’s and General Mills?’ So I asked him back, ‘Well, have you ever heard of David? Have you ever heard of Goliath?’ That went all across California at the time. I’ve always had fun tweaking the noses of our much, much larger competition, thousands of times bigger than us. That hasn’t stopped, and now they’re taking notice.

Defining business ideals

Taking from the Lifestream example, it might be seen that there is a difference in ideals between the founders of natural products companies and the corporations that later purchase them. “The only way big corporations would help the forward stride of the natural products industry,” Stephens said, “is if there were a top- and bottom-line profit and sales growth motive. The moment a company stopped growing or producing profits, they’d probably dump it.”

Profit is often not a central driving force when natural products are developed—a prime example being the first item Stephens produced for Nature’s Path. “The first product we developed in 1985 under the Nature’s Path brand was called Manna Bread, made from sprouted organic grains,” Stephens recalled. “It was based on an ancient Aramaic recipe attributed to the Essenes, a mystical Jewish sect that lived by the shores of the Dead Sea in the pre-Christian era. They left behind these wonderful scrolls, the Dead Sea Scrolls, which eventually found their way into the Vatican Library where they remained for the next 1,500 years or so and were translated.

I was so inspired by them that I decided to try and make a product based upon the ancient recipe that was in these old scriptures. It described sprouting grain and grinding it and leaving it on hot rocks in the desert to bake. Then you make thin loaves of it, and you eat it like your forefathers did when they fled Egypt. They lived in the desert for 40 years. That’s how it was in the beginning. We were all very messianic about spreading the gospel of eating good food and regaining health. There was no ‘industry’ when I started; I don’t think that organic foods in 1967 were more than maybe a million dollars at most all over North America. It was a little cottage industry, mom and pop, with idealistic owners. Today it’s a $60 billion industry. Many of the people along the way maybe lost their ideals or maybe got enticed by the big dollars and they sold out. Then they were horrified to see what happened to their companies afterward. When you sell out a company, it’s almost like the soul gets gutted from it.

This dissimilarity of view was also evident in the recent battle for California’s Proposition 37—the Mandatory Labeling of Genetically Engineered Food Initiative. The interesting thing is that a handful of dedicated companies supported consumers’ right to know what’s in their food,” Stephens said. “Those big giant companies that own natural and organic brands—like Kellogg’s, which owns Kashi, Morningstar Foods and Bare Naked; General Mills, which owns Cascadian and Lärabar—dumped millions of dollars in trying to defeat the citizens’ right to know what’s in their food. For some reason they aligned with Monsanto, DuPont, Dow, Syngenta, Bayer and all these huge global chemical companies. It’s rather amazing.”

True values for strong business

But Stephens himself has arranged it so that his company will never have this sort of experience. “I don’t ever want to have that happen to Nature’s Path,” he asserted. “I don’t want somebody to close down a plant and dislocate a community simply because they want to shift it to some other location, say, in the Midwest, to soak up the capacity of their plants. I want Nature’s Path to remain true to its organic roots and the idealism on which it’s based. My wife and I have been engaged in succession planning for the last few years; we’ve got our son and daughters involved in various aspects, as well as a professional management team. We currently have close to 500 employees.

“I get about 50 inquiries a year—at least one a week—from venture capital companies and those that are fronting for major international corporations that want to buy Nature’s Path, but they end up in the round file. We’re just not interested. We even say on our website, ‘No part of Nature’s Path is for sale.’

“I think what we all want is a better life, and a world that’s habitable for our children, our grandchildren and our great-grandchildren. That’s the bottom line. We want a safer, cleaner, healthier world. PERIOD.”

More information is available at www.naturespath.com.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like