Take these 3 steps to substantiate your dietary supplements’ claims

Supplement brands must make truthful claims—and have the research to back them up—to avoid trouble with the FTC.

A supplement brand has developed a great product and wants to advertise the benefits of that product to the world. But it needs to keep claims on the right side of the line and stay out of the crosshairs of the government.

The Federal Trade Commission is the federal agency that regulates dietary supplement advertising claims. The FTC Act prohibits “unfair or deceptive acts or practices.” This means that any advertising claim must be truthful and non-misleading. To meet that standard, FTC has explained that dietary supplement claims must be substantiated by “competent and reliable scientific evidence.”

The FTC has brought several enforcement actions against dietary supplement companies, and sometimes levied multimillion-dollar penalties and fines. Here are some steps to help brands ensure claims are lawful and properly substantiated.

Step 1: Identify the claims

To determine if claims are substantiated, one must first ask what claims are being made. Identifying “express claims” is easy. Just look what the words in the advertisement say. But the FTC often brings enforcement actions against “implied claims.” These are claims that the advertisement implies but does not state expressly. To see what implied claims are being made, a company must analyze the words, images and sounds. For example, an image of a patient in a hospital bed may create an implied disease claim.

Step 2: Categorize your claims

After identifying the claims, the next step is to categorize the claim. This step is crucial because different types of claims require different types of scientific substantiation.

A structure/function claim “describe[s] the role of a nutrient or dietary ingredient intended to affect the normal structure or function of the human body” or “may characterize the means by which a nutrient or dietary ingredient acts to maintain such structure or function.” One example is, "Vitamin C helps support immune health." To substantiate a structure/function claim, “competent and reliable scientific evidence” is required.

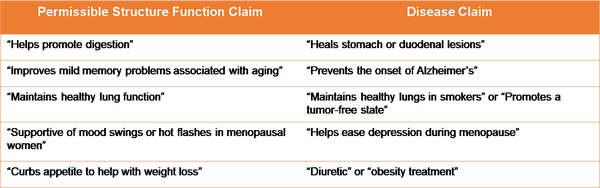

By contrast, supplement manufacturers may not make disease claims. A disease claim states the product can “diagnose, cure, mitigate, treat or prevent disease.” Examples of disease claims include: “cures cancer” or “treats heart disease.” To make a disease claim, a manufacturer must have human, randomized, controlled clinical trials.

This chart contains examples to help distinguish between structure/function claims and disease claims.

Finally, an establishment claim is a statement supported by a certain level of support such as scientific or medical studies: clinically proven, laboratory tested and scientists agree, for example. An establishment claim must be substantiated by the level of support advertised, which is often at least one clinical trial.

Step 3: Determine if the scientific support is sufficient to substantiate the claims

The next step is to analyze whether the science substantiates the claims. Scientific substantiation can come from publicly available literature, proprietary internal research and expert opinion. A careful review of these sources is necessary to determine the totality of the scientific evidence. All relevant studies can be considered.

“Competent and reliable scientific evidence” for structure/function claims includes “[t]ests, analyses, research or studies that have been conducted and evaluated in an objective manner by qualified persons and are generally accepted in the profession to yield accurate and reliable results.” The FTC has explained in its industry guidance that there is “no set protocol” for what satisfies the “competent and reliable” standard and that FTC has drafted the standard to be “sufficiently flexible to ensure …access to information about emerging areas of science.” The commission has further explained that “animal and in vitro studies” can be considered and manufacturers may “extrapolate” results from other studies where the dosage and formulation, administration method and study population are sufficiently similar.

This chart shows the hierarchy of evidence and how scientific evidence can be analyzed.

Benjamin M. Mundel is a litigator at Sidley Austin LLP in Washington, D.C. He represents clients in trial and litigation matters. He has successfully tried several cases against the FTC and other federal agencies. Jacquelyn E. Fradette is an associate at Sidley Austin LLP.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like