February 17, 2017

They say many of the best business plans were written on a napkin. But how many of those plans got their start on a napkin wadded up in a pocket, filled with vitamins?

For Arad Rostampour, the moment he knew he was onto something came when he was pitching his idea for a tech spin on a vitamin business to a potential investor in San Francisco, and the man reached into his pocket, unfurled his napkin, and revealed his daily doses.

It was not uncommon. Rostampour had already seen many other friends with loosely packed vitamins, vitamins they forgot to take, bottles that ran out at different times.

It was, in the parlance of Rostampour’s Silicon Valley business milieu, an industry ripe for disruption.

“This is what got me started,” he says.

Rostampour founded Zenamins, which has come up with a new way to sell vitamins. He’s not the only one. Craig Elbert, who learned about disrupting business when he helped grow Bonobos from a 10-person startup to a 300-person online clothing emporium, has launched Care/of, a company looking to bring the same image branding concepts to vitamin sales. Constantin Bisanz, an Austrian tech entrepreneur, found an enlightened path to health through diet, supplements and meditation, and now his launched-online startup, Aloha, is selling healthy products in Target and other mass-market retailers.

These and other companies are following a path plowed by companies like Uber, Airbnb and Warby Parker: Look for an ossified industry (in those cases, taxis, hotels and eyeglasses), and figure out a way to use technology to provide a similar service that’s easy to use and, in the words of Care/Of’s Elbert, “delightful.”

Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen coined the term “disruptive innovation” in 1995; on his website, he says it “describes a process by which a product or service takes root initially in simple applications at the bottom of a market and then relentlessly moves up market, eventually displacing established competitors.” The term has especially been embraced in the tech industry, which has lowered barriers to entry and made it possible for nimble startups to challenge big companies and entire industries.

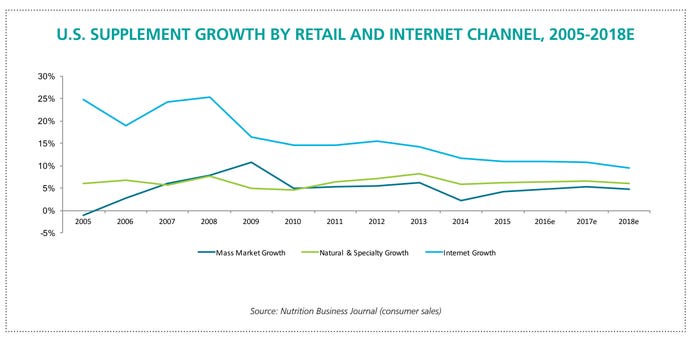

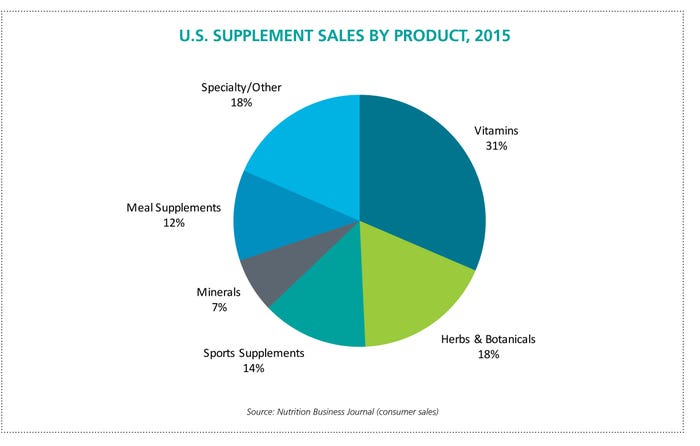

The nutritional supplement and natural products industry is particularly fragmented, from shopping mall retailers like GNC to sales at conventional big boxes and grocers from Walmart on down, with online retailers that range from specialists to Amazon.com, and from mom-and-pop natural stores to Whole Foods Market and other national chains. In addition, consumers are often confused about regulation, product sourcing and a shifting landscape of what anyone should take at any given time.

Meanwhile, new technologies such as DNA testing from 23andme are putting people in charge of their health information. They’re taking a look at their lab tests and deciding what they should take.

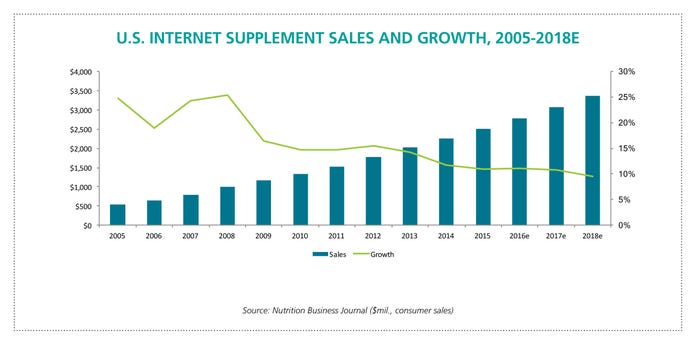

Entrepreneurs look at the situation, as well as some enticing statistics—estimates that more than 70 percent of Americans take vitamins or supplements (according to the Council for Responsible Nutrition’s latest polling), and the market has topped $41 billion by NBJ estimates—and they see a field ripe for disruption.

It’s already happening. In December, GNC said it needed to leave its ��“old, broken model behind,” shuttered all of its 4,464 U.S. locations for a day, and relaunched with new pricing and point of sale systems, as well as a new mobile app.

“We are encouraged by the company’s attempt to stave declines in the business, but see the relaunch as risky,” Goldman, Sachs and Co. analysts Stephen Tanal and Alison Levens wrote in a report. “We believe competitive pressure from the mass channel and online retailers remains intense, and could prove insurmountable if GNC is unable to bridge its shortcomings in convenience and price, or sufficiently differentiate its in-store experience or product offering.”

That’s a challenge several upstarts are eager to exploit.

The direct-to-consumer space isn’t just the best place to lay down that challenge. It might be the only place.

Taking Care/of business

Craig Elbert had abandoned his career as an investment banker by the time he took a job as one of the first 10 employees at a startup in May 2009. The company was selling men’s pants online, and was named for a little-known great ape: Bonobos.

The founders had come out of Stanford Business School, and brought a decidedly high-tech, West Coast spin to their company. The concept: Men hated their pants. They hated the way they fit, and they hated having to shop for them. Bonobos, led by co-founder Andy Dunn, sought to change the entire process, and use the growth of the consumer internet to form a hybrid, a digital company delivering a physical product uncommon to the cyber shopping experience.

Elbert started as director of finance and analytics, and ultimately became vice president of marketing. “The big question was, how do we use technology and the internet to create a delightful experience in a stagnant category?” Elbert says. The product wasn’t particularly sexy; Elbert describes it as “boring khakis.”

“The company was built on how do you have a better product and experience?” he says. “It’s both. We were using technology and human empathy to deliver that.” Because of the rise of social media, Bonobos didn’t even have to spend a ton on advertising. People loved the product and spread the word.

Elbert is bringing that experience and perspective to the vitamin business with his start-up, Care/Of.

“For me, it really started with the experience of trying to shop for vitamins and supplements myself,” he says. “I was vitamin D-deficient. My wife was pregnant and asked me to pick up some prenatals. I went into a store full of vitamins. As a consumer, I felt overwhelmed. What’s the difference between everything that’s in here? Are there other things I should be taking? It was not that easy to sort that out.”

Care/Of’s technology presents customers with a five-minute questionnaire that assesses their goals, health issues, and details about their diets. It also asks whether the customer is willing to take a risk, or only wants recommendations with strong science behind them. It then recommends a regimen of vitamins, with clearly written explanations of the science behind each one. If the customer accepts, Care/Of will mail a packet each month, for a fee, with each day’s dose packed together. With membership, the monthly mailings will continue, so a customer shouldn’t have to think about buying vitamins ever again.

Care/Of avoids the legal challenges common to online supplement outlets by delivering a caveat with its survey-driven recommendations. “We emphasize that people should talk to their doctors first,” Elbert says. “We are not a doctor or a substitute for their doctor. Ultimately, we try to make sense of the research that’s out there, and leave the decision-making to the consumer.”

What Care/Of is trying to replace is that feeling Elbert had when he walked into the vitamin store. Rather than just picking something off a shelf, or quizzing a sales clerk who may or may not know what’s best for any given person, “we want to make that a bit easier by serving up relevant information.”

Care/of, based in New York, raised $3 million from Juxtapose, a New York-based investment fund. Bonobos’ Dunn is also an investor.

The other lesson Elbert brings from Bonobos is to make sure the product looks good—what he repeatedly describes as a “delightful” experience. “It’s important because you often have a world where customer service has been a race to the bottom in terms of how you make something the cheapest. That usually means cutting off customer service and the customer experience.”

By making it fun and beautiful, he hopes to add value to the experience.

Elbert chose the Care/Of name, even with its awkward slash, because of the healthy implications of caring, and for one other reason: As most consumers interact with technology via their mobile phones, Care/Of reaches back to the era of snail mail for c/o, a natural symbol for its app.

Elbert, 36, started his business career in a record shop. And after he left investment banking, he worked for Warner Music during the era when Napster upended the music business. So he has seen disruption from both sides.

“I’ve seen how categories can be disrupted and how the internet can be really powerful,” he says. At Warner Music, “I could see the power of disruption and the challenge organizations face. There are so many hurdles, and incumbents have to move quickly. But they’re full of cost structures. Here, we’re building something from scratch, which gives us certain advantages.”

Going to the Y for Zen

Arad Rostampour’s story sounds like a Silicon Valley classic: He grew up in Colorado, earned a bachelor’s degree at Purdue University in computer science and electrical engineering, and went on to earn two more degrees, a master’s in electrical engineering with a focus on computers at Stanford and an MBA from Wharton. He became an executive at Valley giant Hewlett-Packard before striking out on his own, starting up a company, SocialShield, that helped parents monitor their children’s use of social media. That company had raised a reported $10 million before it was acquired by a large German tech security company in 2012.

Time for the next tech company, right?

Instead, Rostampour took a slot in the Valley’s fabled incubator, Y Combinator, to start … a vitamin company?

Not exactly. “Just like Dollar Shave Club is a tech company shipping razors, we’re a tech company shipping vitamins,” Rostampour says.

Rostampour’s San Francisco-based startup, Zenamins, works much the same way as Care/Of. Consumers go to the company’s site, pick their vitamins, and sign up for a monthly delivery. They’ll get a blister pack with each day’s doses enclosed and labeled. The days are perforated, so if you’re traveling, you only need to bring the days you’ll be on the road. Zenamins will also split vitamins into morning and afternoon packs. These are all smallish tweaks on the blister packs formula, but the tech-style convenience branding makes it stand out.

Rostampour has taken funding, although he won’t disclose how much or from whom. He is working on some large partnerships, including with Pfizer, which accepted Zenamins into an innovation program run by the giant corporation to assist startups on new technological approaches to health.

Some of his bigger tech ambitions didn’t pan out, and some are still in the works. At one point, he hoped to see what nutrients people needed, and then put it all into one pill. While many people prefer the classic one-a-day multivitamin, Zenamins couldn’t fit so many different doses into one pill, and it turns out consumers prefer the individual vitamins. Customers know they’re getting calcium when they see a separate pill for it.

In the future, Zenamins plans to work with doctors and nutritionists, so they can fill out patients’ doses on the site. “We’re trying to make it convenient,” he says. “A nutritionist may write some recommendations on a scrap of paper, and the patient may or may not go to Walgreens and buy the vitamins, and then may or may not take them if they do buy them. We want to make it easy.”

The Aloha way

It’s no longer surprising to see a disruptive nutrition model come out of the direct-to-consumer world. But what if the disruption came from the other direction?

Constantin Bisanz is a serial entrepreneur for whom starting and selling businesses had almost become a game. In 2001, he started TruckScout24, an online marketplace which he sold to Deutsche Telekom. In 2007, he left and started Brands4Friends, an online shopping club. His LinkedIn profile describes how it “grew to $100 million in revenue in less than three years and quickly became the No. 1 shopping club in Germany, the U.K. and Japan.” He sold it to eBay for $220 million.

Still young and now fabulously wealthy, Bisanz took a break before starting his next venture. And that’s when he had his epiphany.

“I worked like crazy all my life,” says Bisanz, now 43. “I always had an interest to be healthy but I found it very difficult.” He would indulge in office snacks, junk food—the standard regimen of an always-on traveling businessman.

“When I left, I had time to dive further in,” he says. “I definitely did not feel healthy.”

He pursued health as relentlessly as he once chased business success. “I said, ‘I want to learn as much as possible from different cultures, ancient philosophy, India, China,’” he says. “I surrounded myself with experts.”

An avid amateur athlete—Bisanz claims to have broken a world record by kite-surfing the Bering Strait from Alaska to Russia—he dove into meditation, yoga, healthy food, and holistic living. That’s when he got the idea for his latest business.

“I spent a lot of time in India studying Ayurvedic philosophy and healthy living,” he says. “It was eye opening, how important food is, and how crappy most of the food is that humans eat.”

Seeing how much of modern processed foods contains sugar, artificial sweeteners and artificial fillers, and talking to doctors and others, “the more I learned from these experts, it was almost like shock therapy,” Bisanz says. “I was angry at the whole industry. I couldn’t find a brand I could completely trust.”

So he created one: Aloha. He began by making protein powders and bars, launching online in January 2014, and very quickly drawing interest from mass-market retailers. One of his first customers was Target. “Usually they start with a test in 200 stores, but they were really bullish and asked us to roll out in all of them.” Target has nearly 1,800 stores in North America.

Bisanz says the big differentiator with other brands is that everything Aloha makes is organic, vegetarian and naturally sourced. “Internally, we are very strict,” Bisanz says.

For the hordes of hopeful entrepreneurs in natural and organic nutrition that may not sound like much of a differentiator. Perhaps, the disruption factor for Aloha is simply extremely solid business practices mated to the mission.

Because of his success in building lifestyle brands in the digital world, he believes he can do the same in nutrition. He’s built a team with industry veterans. Larry Waldman, Aloha’s president, chief financial officer and chief operating officer, once ran the supply chain and operations for Annie’s, the natural foods company that sold to General Mills in 2014 for $820 million. Molly Breiner, the head of marketing, held a similar post at Happy Family Brands, and was a brand manager at consumer giant Unilever.

Or maybe the disruption factor was the confidence from the online success that let Bisanz leap straight into big, perhaps unexpected markets. “People have access to healthy foods on the coasts, in New York or L.A.,” Bisanz says. “Middle America has issues. They don’t know what healthy means. That’s what we’re going for. We want to not only build a big business but also help people. We want to make this aspirational.”

His plans for growth include branching out into an entire lifestyle brand. “We believe there’s a balance between eating healthy food, but also moving, being active in sports and mindfulness,” he says. “We’re going to teach people how to meditate and take care of their personal development.”

Success of that variety, happening online or on shelves, may be the most ambitious disruption the nutrition world has ever seen.

About the Author

You May Also Like