January 1, 2015

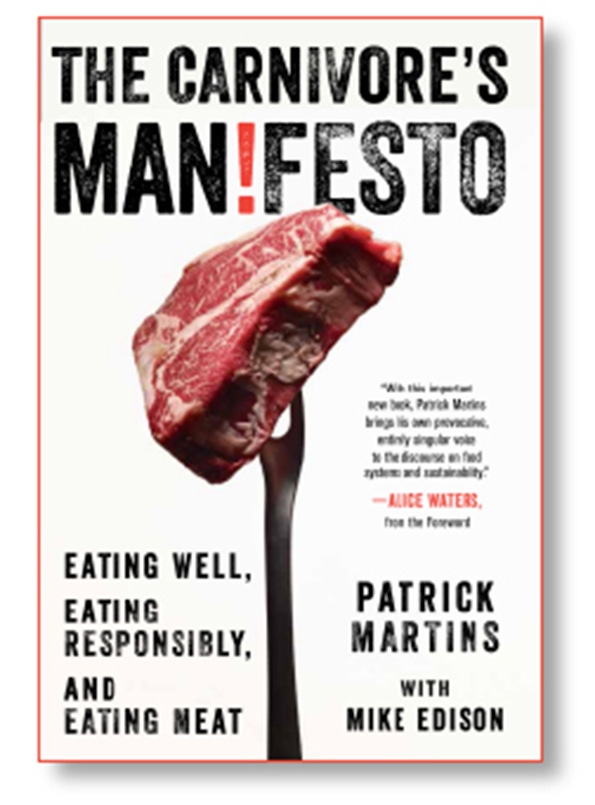

A founder of Slow Food USA, Patrick Martins started Brooklyn-based Heritage Foods USA to provide high-quality, humanely raised meat. In the Carnivore’s Manifesto, he and co-author Mike Edison explain how consumers can shift their shopping and eating habits to bring change to the meat industry. They should eat less of it, Martin says, and care more about where it came from.

nbj: What can people who want to give up meat—or who already have—get from your book?

Martins: For the people who want to give up meat for whatever reason, health, environmental, that’s fine. We’re not trying to launch a campaign for people to eat meat or reconvert from vegetarianism or to start raising more animals. Our argument is that of the 12 billion livestock animals that are processed each year in the United States, 10 to 12 billion need to be treated better. Those animals are being asked to suffer and then die to feed us, and we’re trying to make an argument for the steering of that ship towards a more humane system.

nbj: What about the people who say the resources required are too great for meat and that we should all be eating something else?

Martins: I think that’s an academic question. Eating meat is just a reality, for millions of Americans especially. We let those people debate all they want. Meanwhile, we tried to draw up a roadmap for the majority of Americans who don’t really have those types of discussions on a daily basis. Meat will continue to be eaten in this country. So we want a more humane system where those animals are given more space, where they’re not given antibiotics, and where they come from sound genetics.

nbj: What should people look for when they’re buying meat?

Martins: I think that a little bit of research is always necessary and worthwhile, especially when it comes to meats. I think where you buy it is probably the biggest thing—what restaurants you go to and what butchers you support. I do think labels matter. For me, raised on pasture is number one. Antibiotic free is number two. And the third is heritage genetics. One of the chapters in Carnivore’s Manifesto is “Survival of the Fattest.” Corporations push for fast growth, and they basically create what is an unnatural animal that suffers because of its fat genetics. Its cardiovascular, respiratory, and muscle systems can’t keep up with its fast growth. It’s up to the person to try to find that out, wherever they are, whether they’re lucky and they live in a place like San Francisco, or whether they have access to a FedEx truck and then they can do mail order.

nbj: Give us an example of inhumane breeding.

Martins: All of Perdue’s chickens, all of Smithfield’s pigs, all of the big meat distributors. One of the things we say is, “Don’t buy meat from a publicly traded company.” We know that’s a very hard rule to live by, and we don’t expect anyone to convert 100 percent overnight. But it’s about making the correct choices whenever possible.

nbj: Is the locavore movement doing anything for sustainability and humanely raise meat?

Martins: Yes, absolutely. People are critical of the locavore movement, and I think that is wrong. I think all good movements with their heart in the right place start somewhere and cannot be expected to have the answers to all questions early on. It’s a very young movement, so it should be given a lot of the benefit of the doubt. Its greatest challenge is to arrive at the gastronomic heights of the best of the best, and that takes time. The instinct to want to support your local cheese maker is a good one, but then that cheese maker has to be producing the best of its kind. I also think that the locavore movement has to deliver and service consumers and wholesale accounts, just like Sysco. It can’t hold itself to different standards than what people expect.

nbj: In that group, who is missing the mark?

Martins: Grass fed beef producers have that challenge. The concept is there and everyone agrees with it; now their challenge is for it to taste just as good as the steakhouse steak. And certain people are achieving that. They’re starting to breed for that and figure out ways that are natural and grass-based that can lead to that kind of marbling and things like that. You have to be the best of the best. You can’t be the best of the worst.

nbj: Do you see a tipping point when the mainstream would become more conscious of where they get their meat?

Martins: The tipping point is happening as we speak, thanks to chefs, food magazines, food television, and great restaurants popping up everywhere, and the rise of food trucks. I think that’s all like a kind of whirlpool of energy. It makes sense that professionals—chefs—are the ones leading the way. It was chefs that started my business, Heritage Foods. Chefs were the great funders and supporters of Green Market here in New York. They’re the ones driving it.

nbj: Should we be eating less meat then?

Martins: Yes. I absolutely think the meat should cost more and people should eat less of it. To argue differently is either to not care about the animals or to not care about the people who are eating the bad meat. A lot of people say, “Oh, well, how can a poor person be expected to pay $9 a pound for hamburger meat?” Why would you tell a poor person to eat an unhealthy hamburger? That’s why less meat should be produced. It should be more expensive, and it should be healthier.

nbj: Are consumers misled about humane and sustainably raised meat?

Martins: Absolutely. I don’t think we live in the day anymore where you can just blindly trust that something was raised the right way. You have to question. Go to a trusted butcher and they should be able to tell you all about the genetics. You find out by the breed name, whether there were antibiotics used, if it was pasture raised. Then you should always buy from that same place so that you help keep that farmer in business—not just on Christmas Eve with the roast, but throughout the year.

nbj: Does the new California egg law go far enough?

Martins: I think anything is a step in the right direction. Sometimes I think people who have their heart in the right direction end up infighting or wanting more. And sometimes it’s important to slow down and appreciate that we live in a country where steps like this can be taken and the people have some power to make change. I think it’s a great step. I wish all 50 states did what they did.

nbj: We have written about a slaughterhouse shortage for small farmers. What kind of change is needed?

Martins: More investors need to look at slaughterhouses and food hubs as worthwhile investments, and people need to see that work as honorable and interesting. I think as demand grows more people will see potential in that business plan.

nbj: Is the slow food movement making headway in mainstream America?

Martins: I think so. You almost don’t have to define it. You don’t have to write it in uppercase anymore. They get it. That’s a huge achievement.

nbj: Do you see anything changing across the generations in attitude towards meat?

Martins: I think millennials eat a lot less meat. The days of the 28-ounce porterhouse chop are over. I have a bunch of young kids over and I’m like, “Everybody gets their own 18-ounce steak.” They’ll say, “What? I don’t need that, dude. Just cut me off like a little piece of it.” I do think that’s a big change. I also see millennials being much more creative in the way they get a little bit of meat to feed more people. People are cooking Ethiopian food, and goat leg, and Argentinian molé so it also makes the meat that they eat a lot tastier and interesting.

nbj: Where do you see the meat-substitute category headed?

Martins: I say no good thing comes from doing the opposite of something else. The best approach for people who don’t want to eat meat is to eat foods in the way that the great [vegetarian] cultures have done it. India, the Middle East, those are traditionally non-meat recipes, so for someone to say, “We created ham that tastes just like a ham but it’s not,” I say “Well, the chances of that tasting delicious are low. “

nbj: We are seeing companies that produce vegan and vegetarian products dropping those terms in favor of just saying “plant based.” What do you think is going on?

Martins: I guess what happened is that they put a little too much energy into being against something as opposed to for something. I think the vegetarians learned that the best approach is not trying to get people to stop eating meat; it’s about getting them to enjoy other things and to eat less meat, and to be concerned about humane animal raising. Those are good battles for the vegetarians. If a movement is vilifying the majority of the world, it’s going to lead people to not even use the words “vegetarian” or “vegan.” They were fighting for the right thing, but they weren’t going about it in the right way.

nbj: What is your take on the edible insects movement?

Martins: It’s very interesting. One of the most limitless food supplies in the world is anchovies that come out of the Antarctic. Of course the academics are like, “Wow, wouldn’t it be great if China, or poor people, could eat these anchovies and enjoy them? It would be the cheapest and most abundant food source in the history of the world.” I think the insect movement has that a little bit too. It’s like, “If only...”

You May Also Like